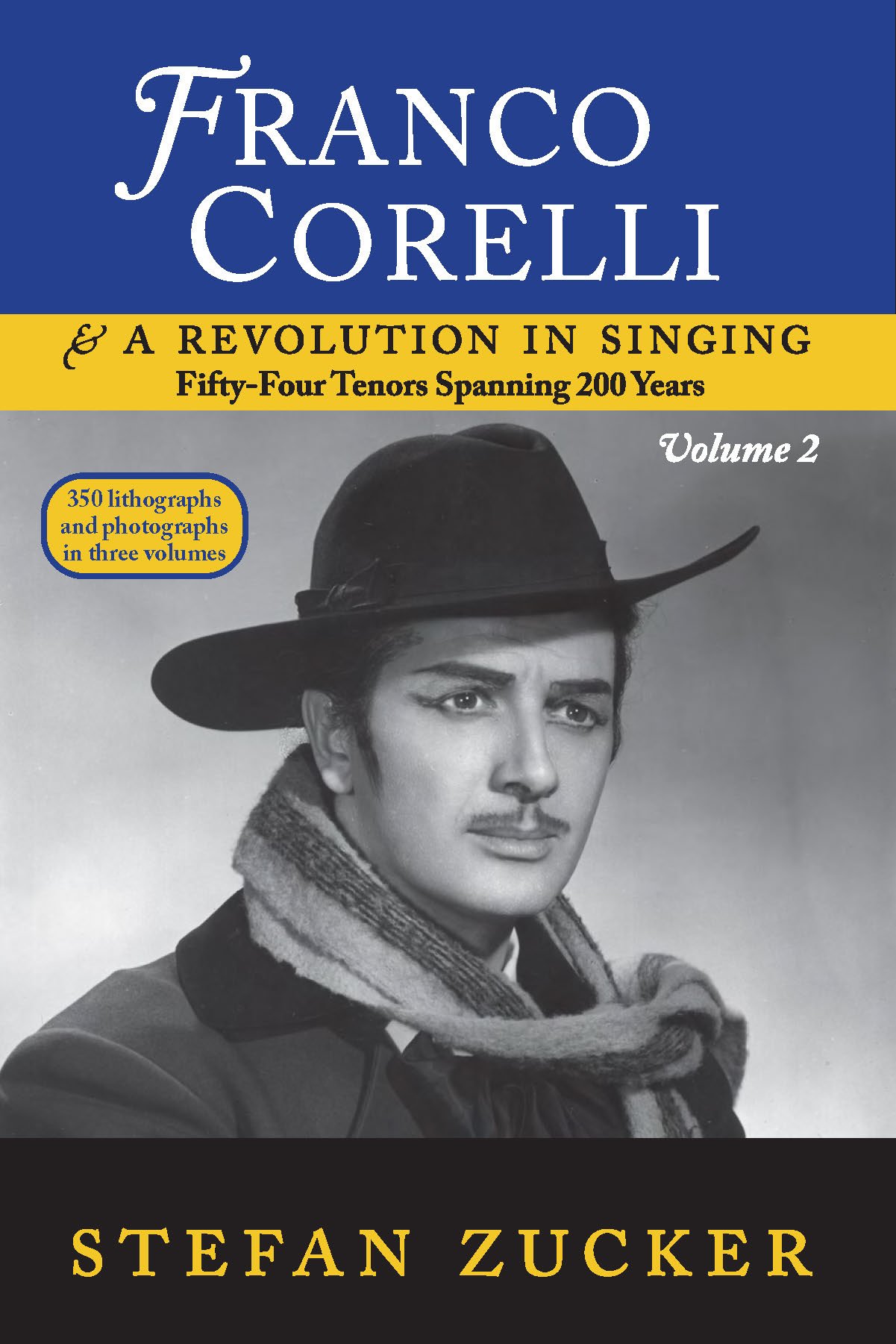

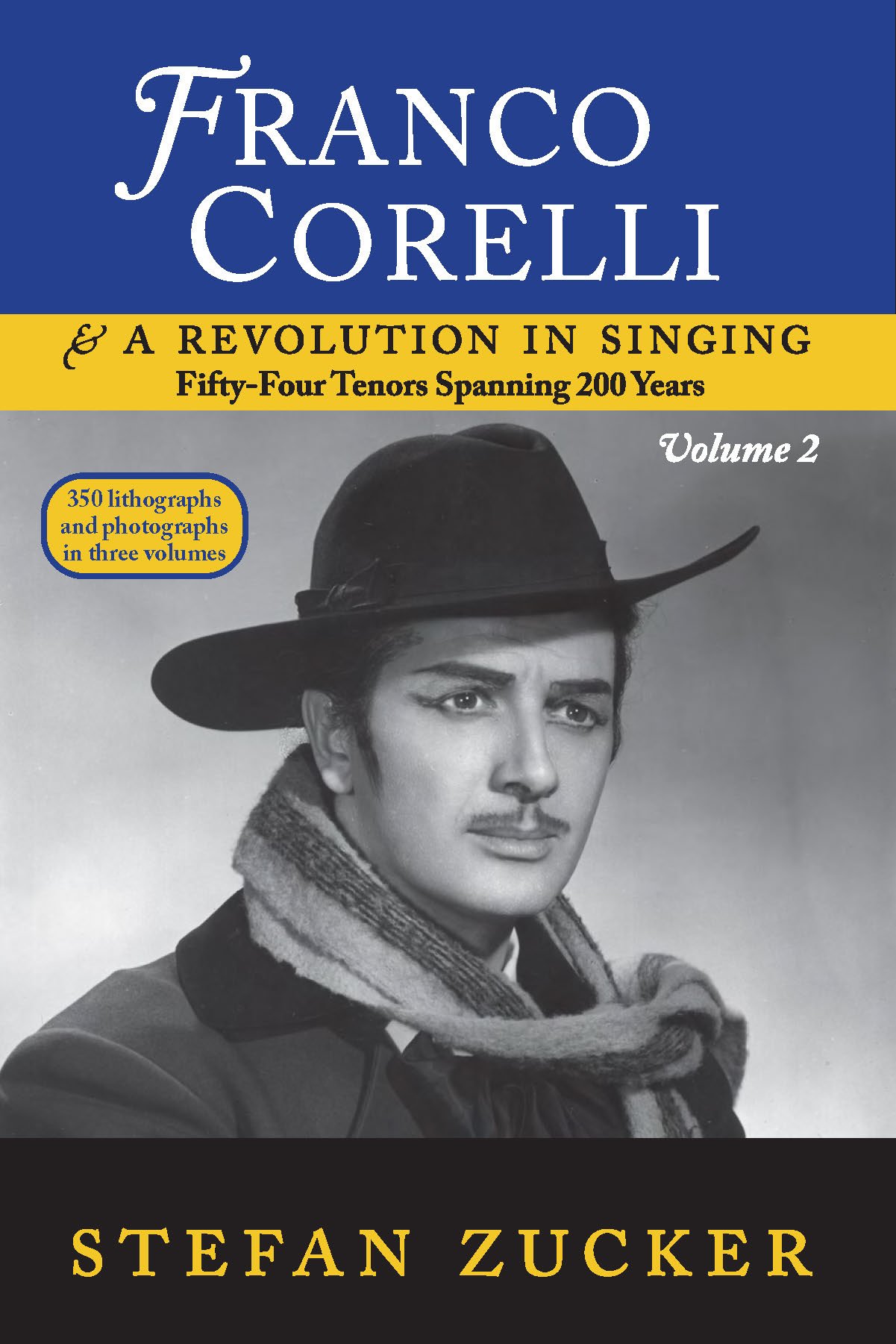

ISBN-13 : 978-1-891456-03-9

351 pp, published in 2018 by Bel Canto Society. Click here to order the book

FRANCO CORELLI & A REVOLUTION IN SINGING VOLUME TWO by Stefan Zucker

ISBN-13 : 978-1-891456-03-9

351 pp, published in 2018 by Bel Canto Society. Click here to order the book

Everything Jan Neckers wrote down in his review of Volume One in this series (click here) can sadly enough also be applied to Volume Two. The present opus is written and compiled by a man who is full of envy towards other Corelli authors, is a victim of self-aggrandizement, loves inventing, and changing or fabricating stories, takes his wishes for granted and is sexually obsessed. Let’s face it, how sincere can you take a book written by a man who unashamedly defines himself in the cover’s biography note as an “under stud” for Corelli?* Seriously?

Moreover, much of Zucker’s research (sic) boils down to “I was told”; in fact “I was told” would have made an appropriate subtitle for the book. Besides, who on earth is willing to spend US$34.99 + postage for a book dealing with the origins of an “Italian version” of a blowjob and Corelli’s allegedly obsession with it. Sex always sells or what? From pages 259 to 276 the vocabulary ranges from sex, blowjob, deep throating, vagina, prostitutes, penis size, orgasms to even anal sex. Additionally, envious Zucker especially devotes three (!!) chapters to dish other Corelli biographers starting with René Seghers (who wrote the only serious Corelli biography) Marina Boagno to poor Giancarlo Landini. The latter is painfully reproached for the poor quality of printing and photos. Now everyone possessing the Landini book knows this is a high-quality publication and is nothing of the sort Zucker claims it to be.

In fact, contrary to most of the photos in Zucker’s Volume One, the ones in Volume Two are unexpectedly of inferior quality and only two of them are new to me. Not only here does the pot call the kettle black. Zucker in his crusade against the other Corelli book authors is more than eager to point out ‘errors’ and ‘typos’ in their works. But what to think of an author who has Adolphe Nourrit commit suicide in 1939 (pg.35) or painfully mislabels a Del Monaco Manrico photo for Ernani (pg. 320)? Sandra Warfield and James McCracken didn’t write their autobiography in the book “A star family” as Zucker claims on page 231. “A star in the family” is a candid, open-hearted, exciting and funny diary of one year in their lives but it is certainly not a full autobiography.

Redeeming factors. Hardly any; even when Zucker keeps himself under control and restrains himself the quality of his writing is less scholarly than usual. This is especially clear in his discussion of several of Corelli’s recordings; not surprisingly a promo stunt, as most of the releases are Bel Canto Society products. This chapter could have made the book invaluable as in the Ardoin-Callas legacy sense but that would have meant work and effort, something Zucker did not invest. Sadly enough, Zucker, who admittedly possesses the capacity of writing with great expertise on singing and singing technique, limits himself to “larynx this or larynx that” ad infinitum. Speaking of a 1967 rendition of “E lucevan” Zucker professes it to be “the most sensual of all live tenor recordings of the twentieth century?” Really ALL live tenor recordings of this aria? Are you kidding me?

Zucker is much better in the first rehashed chapters on Rubini, Nourrit and Duprez though also these previously appeared in Opera News and his own Opera Fanatic magazine. Of interest too is the chapter (p.167 – 221) containing several of Corelli’s letters from 1962 till 1973 to his mentor Lauri-Volpi. These were new to me.

Another chapter deals with the Corelli/Del Monaco rivalry and readers will delight in the selected correspondence (provided by the Metropolitan Opera Archives) between Rudolf Bing and Roberto Bauer on the matter. Zucker, regrettably, reproduces only part of the correspondence which continues up until 1965 (Zucker ends in 1964) and nowhere does he analyze the content or place the letters in the right context as Seghers has done in Prince of Tenors, where most of these letters were first presented.

Interesting too is the chapter – contributed by John Pennino of the Met Archives — of what both Del Monaco and Coreli were paid by the Met. Yet again Zucker doesn’t do anything with it as he should have put the whole chapter in a broader perspective by telling us what Bjoerling, Tucker, Callas, Tebaldi and Bergonzi, for instance, were paid in those years when they were on the roster.

Oh, yes the book is printed on the same high quality paper as Volume One but I still have to meet the first person who buys a book just because of that.

Rudi van den Bulck, February 2018

*

““for the sake of the Corelli’s marriage, at Franco’s behest he (i.e. Zucker) made love to some women who were chasing him”.