RICCARDO STRACCIARI part one

1. A brief outline of the Artist

Emilia-Romagna is a land in the Northern part of Italy where cattle-breeding is a diffuse activity, upon which a food Industry has flourished in the centuries (‘salami’, ‘cotechino’ etc.. .are well known worldwide in cookery).

Casalecchio di Reno, a village in this land, had the privilege of giving birth in 1875 to Riccardo Stracciari, a baritone-to-be.

As is a common saying in Italy, Emilian people are extrovert, friendly and of open-character, but sometimes prone to sudden outbursts of rage even for futile reasons.

This does seem to apply to Stracciari only for the first part of this profile, according to people who had been acquainted with him (see the parallel contribution by Luciano DiCave devoted to direct relationships with him, anecdotes,etc..): no ‘volcanic’ attitudes however have been reported on the account of his temper.

Surely the atmosphere inspired by his singing, so quiet, so clear and on the whole well-balanced is opposite to what could be expressed by a hot-blooded temper.

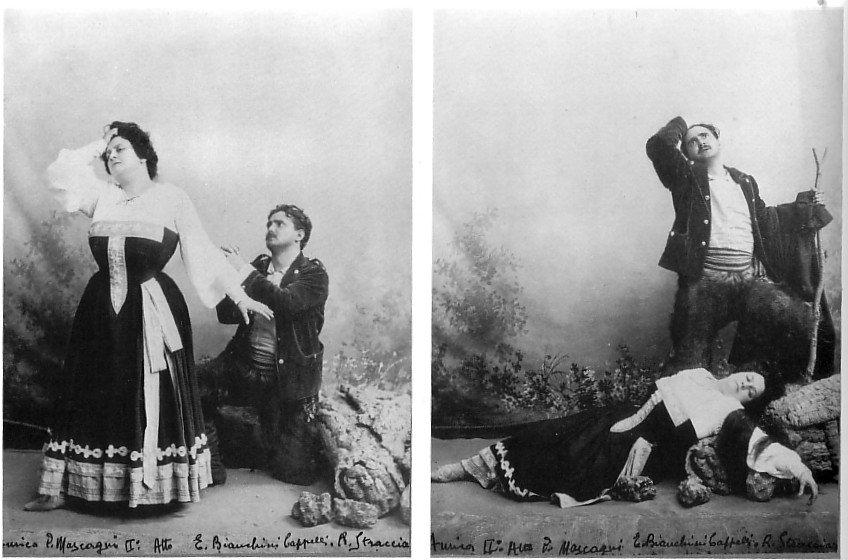

Pupil at the ‘Conservatorio di Bologna’, his first steps were as a chorus-singer in an ‘operetta’ Company. He made his debut at the Bologna ‘Comunale’ in Perosi’s ‘Resurrezione di Cristo’ in 1899. The first important performances were ‘Traviata’ and ‘Aida’ in Lisbon, to be followed by appearances in the most famous Italian Theatres (Comunale di Bologna, Opera di Roma, La Scala).

From now on an international career started in the most important countries around Europe, South America (Buenos Aires) and North America: here he took part in two Seasons at the Met, in 1906-07 and 1907-08. Later on (1917-19) he returned to Chicago (Auditorium) and New York (Lexington Theatre).

His career was long (his last public appearance was at ‘Comunale’ di Como with ‘Traviata’ in 1944), spanning over forty-five years.

He died in 1955, at the age of eighty.

2. Stracciari and his contemporaries

The years from 1875 and 1878 were really singular –fortunate, for the lyric destinies- since four excellent baritones poured in, at the rate of ‘one per year’; namely: just Stracciari (1875), Giuseppe DeLuca (1876), Titta Ruffo (1877) and Amato (1878).

This period followed the generation of Kashmann and Battistini.

This last in particular was highly representative of the 19th century ‘belcanto’ with large use of vocal ornaments and all the other tools deemed important to flavour the expression.

DeLuca, not particularly gifted as vocal means, basically followed a Battistini scheme: the voice had similar tenor-like colours, but the attitude was different, more genuine and open to the modern feelings: no ornamentation disconnected from true expressive motivations. To summarize, an intelligent and refined singing.

Titta Ruffo followed a line of his own, being a real outsider: titanic voice, phenomenal extension, great dramatic attitudes. He preferred a direct and aggressive singing, in line with the then dominant veristic environment.

Some similarities can be found between Amato and Stracciari, both representing a true ‘tongue’ between the opposite requirements of ‘belcanto’ and dramatic interpretation: both possessed a fluent voice, sense of equilibrium, complete control of the technique.

Few decades later Benvenuto Franci would have revived the dramatic baritone figure with strong characterization of some ‘cattivo’ roles like Barnaba, Scarpia and so on, while his counterpart, Carlo Galeffi, would have properly impersonated the role of the gentleman (baritono ‘signore’).

3. Voice, technique and interpretation

What immediately strikes in the Stracciari vocal organization is the soft and velvety timbre, superimposed to a voice of great compactness and solidity.

Often the S.timbre was said to be ‘throaty’. This peculiarity has been underlined by several critics, among whom Rodolfo Celletti [‘Le grandi voci’]:

‘..il fondo gutturale,che rientrò sempre nel timbro di S., rende il suono caratteristico e personalissimo nei dischi del miglior periodo e si muta quasi in pregio; ma nelle ultime incisioni appare in modo accentuato e scoperto’.

[..The throaty nature, which has always been a part of the S. timbre, makes the sound ‘characteristic’ and ‘strictly personal’ in the records of the best period, reverting to a merit; however, in the last recordings, it springs up in a emphasized and open way].

Surely a vocal production basically ‘throaty’, as existing in artists of less qualified range, tends sometimes to mask an improper use of the technique, privileging thoracic resonances instead of focussing the sounds in the ‘mask’. Obviously this does not apply to Stracciari: here we deal with a pure timbric colour, not absolutely with technical deficiencies.

With regard to technique………

The homogeneity of the S.voice throughout the vocal extension [t.i.the capability to span over the whole range of sounds up to the extreme notes of the baritonal score without variations in the colour or ‘whitening’ or ‘opening’ the sounds] is a heritage of the great ‘belcanto’ school.

But, beyond voice and technique, an almost common feature of the S. records are artistic intelligence, style, and taste which leads the Artist to avoid excesses in interpretation which, apart from disliking the listener, invariably would influence the voice production, causing lack of sound balance.

But perhaps paradoxically just his wrapping timbre risks to obscure his interpretative features. The repeated and consecutive hearing of his records, for instance, might lead the listener to rejoice in a world of heavenly sounds, thus avoiding to outline the different situations and characters from time to time conveyed by the Artist.

Is it not perhaps natural the immediate seduction that the looks of a very beautiful woman can raise, even if subsequently, in cold blood, one can recognize also her intellectual capabilities?

4. The great romantic composers

The velvety quality of S.timbre, the great capability to flow over long melodic lines with complete breath control and the overall equilibrium in the sound distribution naturally make the S. voice ideally suitable to interpret the characters of the romantic composers.

Two examples can be taken from the vast amount of records made by S. and fortunately preserved for our pleasure: Favorita and Faust.

In both cases the characters are of high descent: their invocation, whether to a beloved woman or to God himself, require noble accents, restrained emotions and great dignity.

If we consider the aria ‘Vien Leonora’ from ‘LA FAVORITA’ by Donizetti, it is possible to note the regality and the beauty of tone inherent in Alfonso’s message to Leonora: the first part of the Aria is concluded in an aerial whisper which suggests a variety of colours in the second part of the Aria itself; but…..Where is the second part? Here a first charge to Riccardo!

Why has he properly recorded this 2nd part but prevented its publication?

Twice he recorded the 1st part (early for Fonotipia and later on for Columbia), but in both cases no trace has been found of its sequel.

Let’s go to ‘FAUST: Dio possente’. The early recording for Fonotipia, despite the absolute fitting of the music to his temper and with the voice at its peak, in my personal opinion is a bit disappointing: generic expression, apparently not a great feeling and a slight rush. Of course one must take into account the roughness of the recording technology of those times and –about rush- the need to contain within a few minutes the whole musical part.

Then give to Riccardo a second chance! Rerecording of the aria for Columbia, eight years later. Everything now fits: voice and interpretation, exactly as we originally would have expected from him.

The invocation to God to protect Margherita is really the prayer of a man to a God : sweet, submissive.

What a different attitude displayed –for the same aria- by Titta Ruffo, who seems to address the God as –at least- a semi-God, partly asking, partly pretending!..

Marvellous, both performances!