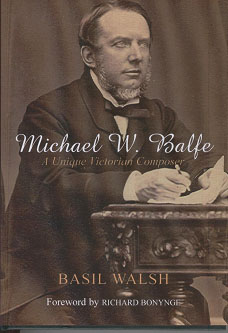

Basil Walsh (1934-2014): MICHAEL W. BALFE

A unique Victorian composer

Irish Academic Press

The subtitle of this biography is: “A Unique Victorian Composer” and the least an author can do is to prove this grandiloquent allegation. In vain the reader will find proof that Balfe’s compositions were unique unless the writer thinks Balfe’s tireless work as a singer, a conductor, a traveller to earn the necessary the money to live in style (4 servants) is unique for the Victorian Age. But on the kind of music he wrote we learn next to nothing. Therefore we have to ask: why did these unique compositions go into oblivion ? There is a small phrase at the end that maybe is revealing. Balfe’s last opera Il Talismano, first performed four years after his death in 1870, was “reminiscent of early Verdi”. In other words Balfe was still composing à la Bellini and Donizetti (whom he knew personally) when Verdi had already written Aida. But for a judgment of Balfe’s music, the reader won’t find a clue in this book and therefore has to listen to the commercial recordings of The Bohemian Girl or the recently issued The Maid of Artois. It is easy, charming music which doesn’t ask too much of the listener and it has some nice tunes though it will be difficult to remember them afterwards (with the exception of that single moment of genius which is the aria I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls). Balfe therefore reminds one somewhat of the youthful and lesser inspired compositions of Donizetti and he definitely doesn’t have the talent of contemporaries like Boieldieu or Adam.

This biography follows the (sometimes) tedious path of “and then he went” “and then he conducted” etc.etc. Granted, most composer’s lifes are written in this way but most composers had a somewhat more exciting existence or lived in times that had more challenges. This isn’t the author’s fault and as Balfe was somewhat forgotten, some of his traces were wiped out. Therefore Walsh continuously has to use words like “no doubt that” or “probably”. Still, this doesn’t mean that the author delved deeply into the society where Balfe lived. Walsh writes that there is no official certificate to be found of Balfe’s marriage in Bergamo because Lombardy at the time was Austrian and “probably” all records went to Vienna and were subsequently lost. Come on. All catholic marriages were and are still registered in the parish and kept there. Vienna would have been double in size if they had to keep all parish records from all countries the Hapsburgs governed. A problem with a Roman count further in the book tells us the author asked someone local to solve it. Therefore we may easily deduct Walsh doesn’t know Italian and didn’t do research in Italy on Balfe’s Italian years. Footnotes too are not the author’s strength. Almost every page he interrupts his narrative and introduces in four or five sentences someone or something of minor importance which ought to have appeared in a footnote. I have the feeling this is a means to make the biography itself somewhat longer and more voluminous. Even now it doesn’t exceed 180 pages. The annexes take another 116 pages. Some of them are very interesting like the list of compositions, the operas Balfe conducted or sang. Others are somewhat strange like the list of every (sometimes small time) singer who performed in a Balfe opera while the singers in the recording of the Bohemian Girl have to do with “international cast” without any names.

One last grumble. Mr. Walsh’s grasp of history is a bit shaky. We read that queen Victoria’s ascent had “enormous consequences for England and its Empire.” If so, I would dearly have liked to know them. The UK was firmly in the hands of government and parliament. Wellington, Palmerstone or later on Gladstone and Disraeli wouldn’t have thought for a moment to imply a policy, wanted by the Queen, if this would have gone against the interests they perceived to be the best for the country. And I can assure Mr. Walsh that Balfe’s son-in-law probably didn’t leave Danzig in 1860 because of Bismarck’s policy of unification as Bismarck wasn’t even in office (he was an ambassador to Russia until 1862). Geography isn’ t Walsh’s forte either. He notes that The Bohemian Girl came home when it was played in Pressburg in Bohemia. Maybe it wouldn’t have been a bad idea to tell British readers that Pressburg is nowadays Bratislava ( capital of Slovakia )while one look at an historical atlas would have told the author it belonged to the kingdom of Hungary and was never part of Bohemia. In short, even a minor composer deserves somewhat better.

Jan Neckers, Operanostalgia