GIACOMO RIMINI, A BIOGRAPHY BY CHARLES MINTZER

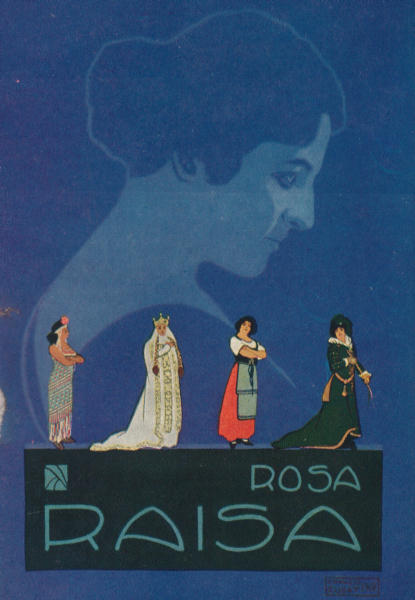

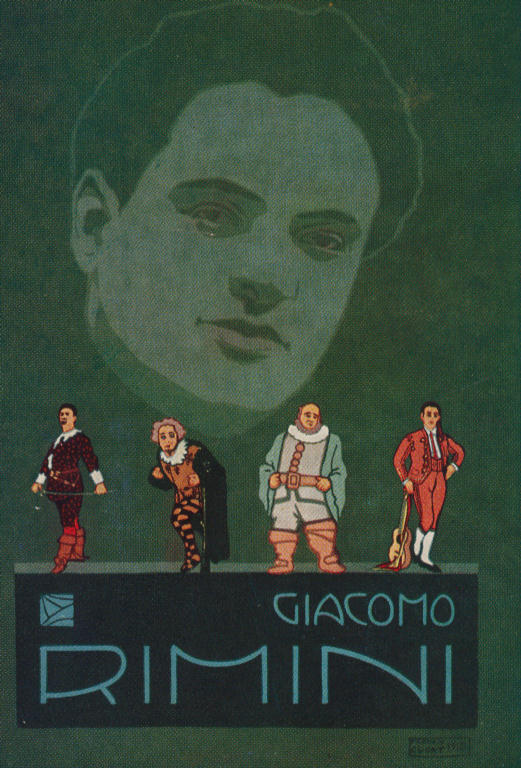

Operatic artists of an earlier era are today remembered, if at all, for either their unique artistic profile and accomplishments, or they may be remembered by their associations. Giacomo Rimini’s name is most often mentioned as the husband of Rosa Raisa, with whom he shared a joint career: his own not inconsiderable achievements are most often treated as footnotes to those of his more celebrated wife. (An internet search (“Google”) of “Giacomo Rimini” yields mostly “hits” for the 1932 Falstaff recording or as the husband of Rosa Raisa, virtually none for his own career.)

Ask any reasonably informed opera lover with a good knowledge of performing history who Rosa Raisa was and they will tell you that she was the creator of Turandot and reportedly possessed one of the all-time big voices; ask the same person who Giacomo Rimini was and you will be told he was the husband of Rosa Raisa. Husband and wife couples are not unusual in operatic history. Rarely is there equality in either talent or stature in one of these couples. Names of such couples will occur to everyone. However, few of these partnerships were so totally linked as were Raisa and Rimini. For most of their careers, at the end of every single day, they went home together. Rimini, before he met Raisa in Milan in 1915, may have eventually been reckoned a worthy Italian baritone of just under the first rank, but it is doubtful that, in an age of so many truly great Italian baritones, he would have stood out other than for his Falstaff and a handful of singer-actor roles. It is of interest that, in both the LP era and in the current CD era, Rimini’s recordings, other than the 1932 complete Falstaff, the duets with Raisa, or an occasional track on an historical anthology, have never been reissued as a comprehensive collection. (When Ellen Lebow, producer of the “Club 99” LP series of singers of the past, asked me (circa 1970) to recommend some artists, not yet issued, for new LP consideration, she vetoed my suggestion of Rimini, suggesting he was “not first rate.” She did produce two LPs devoted to Raisa. This appears to be the overall “take” on this baritone.)

Who was Giacomo Rimini? He was born in Verona on 26 March 1888 to middle-class parents, Riccardo and Giulia Sottopera Rimini. Riccardo was descended from Sephardic Jews long resident in Verona (Mark Tedeschi, The Jews of Verona, article published by the Philadelphia Jewish Genealogical Society, 1983. E-mail of 7 August 2002, Mark Tedeschi (of Australia) wrote, “I have a Giacomo Rimini in my family tree, but not the one you mention.” Professor Decio Levi (of Bozzolo) e-mailed on 26 July 2002 “usually city names in Italy are considered to be Jewish.”) and Giulia was an Italian with a Hungarian mother. Giacomo was raised in his mother’s Roman Catholic faith. Eventually his religious background would play off against Raisa’s strong Eastern European traditional Jewish orthodoxy in interesting ways. Giacomo studied singing with a celebrated nineteenth century soprano, resident of Verona, Amelia Conti-Feroni. Conti-Feroni in her day was a noted dramatic soprano counting Aida, Amelia in Un Ballo in maschera, Abigaille in Nabucco, Leonora in La Forza del destino, Norma, Gioconda, Rachel in La Juive, Lady Macbeth, Donna Anna in Don Giovanni, Valentina in Gli Ugonotti, Leonora in Il Trovatore, and Paolina in Poliuto among her roles on the stages of Italy, France (Théâtre Italien) Iberia, South America and Eastern Europe. She was also the teacher of Augusta Concato.

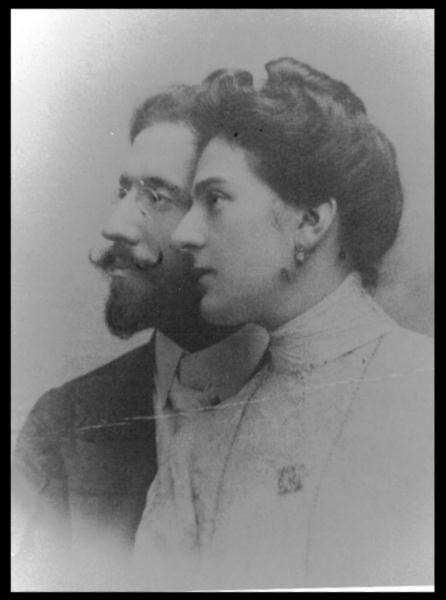

(Rimini's parents,Riccardo Rimini was for a time the president of the small Veronese Jewish community and he's buried in Verona's Jewish cemetery. Rimini's mother is buried in the municipal cemetery of Verona-ostensibly non-sectarian but essentially Catholic)

(Rimini's parents,Riccardo Rimini was for a time the president of the small Veronese Jewish community and he's buried in Verona's Jewish cemetery. Rimini's mother is buried in the municipal cemetery of Verona-ostensibly non-sectarian but essentially Catholic)

In 1910 young Giacomo made his debut in the town of Desenzano on the southern tip of Lake Garda, near his home city of Verona. He sang the role of Albert in Massenet’s Werther. Little is known of this debut assignment, neither the exact date nor even the names of his colleagues. Clearly, he was encouraged from his success to go on to engagements in the relatively small theatres of Rovigo, Sassari, Pistoa, Fiume, Regio Emilia, Modena, the Biondo in Palermo, and the Malibran in Venice. The one major theatre in which he performed in this period was the Regio in Turin as King Raimondo in five Isabeaus. Another early role was Rance in Fanciulla del West, in the recent (1910) Puccini opera, suggesting very early on that leading roles in which acting is a major factor was possibly his calling. In April 1913 he graduated, singing in Paris in some of the inaugural performances at the new Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, with Maria Barrientos in Lucia di Lammermoor and Il Barbiere di Siviglia.

His career gathered momentum and he moved from the good but smaller Italian houses to some international engagements, even if not yet in the top theatres. He ventured to Stockholm for a stagione of Italian opera; there his most noteworthy colleague was Elvira de Hidalgo. During the last half of 1913 he made his first of what were to be five voyages to South America, first in Santiago and Valparaiso, Chile, and later in Buenos Aires at the Teatro Coliseo. He sang there with sopranos Matilda de Lerma and Elsa Raccanelli, and with tenor partners of the calibre of Florencio Constantino and the rising Aureliano Pertile. His career moved forward a considerable degree when he returned to his native Italy for engagements at the Massimo in Palermo, the Carlo Felice in Genoa and the Costanzi in Rome. Milan’s Dal Verme, where he had a big success in 1914, re-engaged him; this time they were presenting an extraordinary season under Toscanini, who had just returned to Italy from his seven years at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Toscanini was so impressed with Rimini’s gifts and potential that he personally taught him the role of Falstaff. With him in the seven performances of Falstaff were Maria Farneti, Ines Maria Ferraris, Virginia Guerrini, Tito Schipa and Ernesto Badini. This glamorous Dal Verme season was the one that saw Enrico Caruso’s last stage performances in Europe. Rimini had sung at the Dal Verme from September to November 1914: 19 performances of Jack Rance in Fanciulla, with Carmen Melis and Giulio Crimi, 6(?) of Escamillo with Rosita Cesaretti as Carmen and Crimi as Don José and 8 performances of Don Carlo in Ernani, with Maria Wroblenska, Giacomo Maniero as Ernani and Enrico Molinari as Don Ruy Gomez de Silva; all performances conducted by Baldo Zenoni. Puccini attended at least one of the Fanciulla performances, probably the première. He greeted Rimini backstage and presented him with a photo, inscribed: “all’ego artist Giacomo Rimini in ricordo del grand Rance al Dal Verme Sett. 1914. Giacomo Puccini.”

In season 1914-15 at both the Massimo in Palermo and at the San Carlo in Naples he performed Scarpia in Tosca with the ascending star Beniamino Gigli, who became a life-long friend and performing colleague in South America in 1921. Often in New York when the Chicago Opera played seasons there in the early 1920’s they met socially and performed together there in concert in 1923. On 18 March 1923 Gigli and Rimini sang a joint concert with Gigli’s teacher/coach Enrico Rosati at the piano; this concert was at a communion breakfast at the Commodore Hotel in New York City, for a New York City police Catholic society. 3,000 police were present at this concert. 1933 found them together both in Rome and in the famous Berlin stagione, and finally Gigli was a guest at his daughter’s wedding in 1950.

In the winter of 1915, while singing Francesca da Rimini at the Corso in Bologna, Raisa was urged by her mentor and friend Margherita Clausseti, daughter of legendary Carlotta Marchiso, the niece of her teacher Barbara Marchisio and wife of Carlo Clausetti, general director of Ricordi’s, to attend a performance of Falstaff at Milan’s Dal Verme, suggesting that Raisa should meet the young and handsome baritone Rimini who was making a great success in the title role. An anecdote Raisa told for many years was that when she visited the baritone for the first time backstage she could not immediately appreciate through the padded costume and unattractive makeup that he really was quite young and very good-looking. In any event the two young artists met and were clearly smitten with each other; in short order they became inseparable friends and lovers, although they would have to wait five more years before they could legally marry. Rimini’s very religious mother Giulia had forced him to marry Delizia Capuzzi, the mother of their daughter, Rafaella. (Giulietta (Jolly) Rimini Segala, daughter of Raisa and Rimini, told me this bit of family “dirty linen”, when I interviewed her in Santa Monica, California in October 1983.) He supported Delizia and Rafaella after he and Raisa in effect became a couple enjoying a joint career. Starting in 1916 their activities in South America, at the Chicago Opera, and in concert in the USA were always joint undertakings. Raisa’s star status ensured Rimini’s engagement, and at a handsome salary, wherever she sang. The insistence that they always be engaged together probably accounts for the omission of her name on the roster of the Metropolitan Opera.

Before appearing in the United States for the first time in the autumn of 1916, Raisa and Rimini launched their joint careers in Rome on 23 March in Aida and on 28 March in Francesca da Rimini, and then embarked on their first of four joint tours of South America. In Buenos Aires at the Colón he performed Amonasro in Aida, Renato in Un Ballo in Maschera, Rolando in La Battaglia di Legnano, and Hermann in Loreley, all with Raisa. Giulio Crimi, Tito Schipa and Giovanni Martinelli were the featured tenors in that season. Additionally he performed Gérard in Andrea Chénier, with Gilda Dalla Rizza, and Enrico to the Lucia of Maria Barrientos. Some of these operas were repeated in Montevideo, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In Montevideo Rimini created the role of Duque de Bouffers in the world première of a rarely performed opera, Cortinas’s La última gavota, with Gilda Dalla Rizza as the Duquesa de Bouffers and Tito Schipa as Caballero de Saint Lambert. The three principals were highly praised, considering that the new opera was mounted with very few rehearsals. And in Rio he sang his first ever Falstaff with Raisa. Titta Ruffo had performed the title role (his first anywhere) of Verdi’s comic masterpiece earlier on the tour in Buenos Aires. These Falstaff casts also included Ninon Vallin, Tito Schipa and Armand Crabbé. They would sing this opera thirty-three times together during their careers in many different venues; it was important to Raisa to participate in an opera where Rimini was clearly the lead character. Upon the conclusion of the tour in which Rimini sang forty times in four months, he came to the United States and went to Chicago, the couple’s real artistic home for the rest of their careers. They eventually become American citizens in 1923.

For an artist who was to sing for sixteen consecutive seasons and several hundred performances, both in Chicago and on the company’s famous transnational tours, Rimini’s debut on 13 November 1916 in Aida with Raisa and Crimi elicited only general and qualified comments. Karleton Hackett in the Post thought that “one can not be quite so sure. His voice is agreeable in quality and he stands well upon the stage, but it had not last night quite the expected vibrancy and solidity. So we shall have to wait a bit and hear him again.” Since Rimini was Chicago’s lead Italian baritone this season, the wait was very short as two nights later he was Gérard in Andrea Chénier, again with Raisa and Crimi; Hackett thought “Mr. Rimini was much better suited by the music and the part he had to play than on the opening night, and while his voice is a little somber in color and not always steady, he did some excellent singing and ought to prove a valuable addition to the company.” Rimini was the Rigoletto in the famous 18 November Saturday matinée that gave birth to Amelita Galli-Curci’s dazzling international fame. The Musical Courier thought that Rimini “did better than heretofore and sang himself into the hearts of the listeners, albeit the tremolo was present again.” In Pagliacci on 23 November Rimini enjoyed his first genuine success of the young season; the Courier noted: “The “Prologue” was well rendered and had to be repeated. Mr. Rimini, as stated in these columns, is a far better actor than a singer, and histrionically his Tonio could not be improved upon…only here and there, especially in the high register, was the vibrato and tremolo noticeable.” Falstaff on 18 December drew a small house. The Courier noted that “Verdi’s comic opera does not please the public. It may laugh and say the opera is funny, but in reality is bored and undemonstrative.” Even with Campanini in the pit and Raisa as Alice, the public viewed this opera, at least in Chicago, and probably even in New York with Toscanini, Destinn, and Scotti, as a work one is ‘supposed’ to, rather than actually, like (The box-office receipts for the Falstaff of 20 March 1909 at the Met with Toscanini, Destinn, Alda, Grassi, Scotti, Campanari was $8082. Around this performance there was an Aida that took in $9423. A Pagliacci without Caruso that brought in $8908, a Bartered Bride with Destinn under Mahler, $9173, and a La Bohéme with Farrar and Bonci that brought in $10,492. Figures are courtesy of the Metropolitan Opera Archives.) The inclusion of an opera such as Falstaff in the Chicago Opera repertoire indicated that not only with Mary Garden’s French operas was the company able to present sophisticated and musically complex works. Regarding the performance the Courier was impressed by “the excellency of his acting. His makeup was good and he was more successful vocally than heretofore.”

(Rimini-Stracciari-unknown-Mme Stracciari-Zenatello-Bottom: Campanini-Maria Gay-Eva Tetrazzini-unknown-RR-NJ1917)

(Rimini-Stracciari-unknown-Mme Stracciari-Zenatello-Bottom: Campanini-Maria Gay-Eva Tetrazzini-unknown-RR-NJ1917)

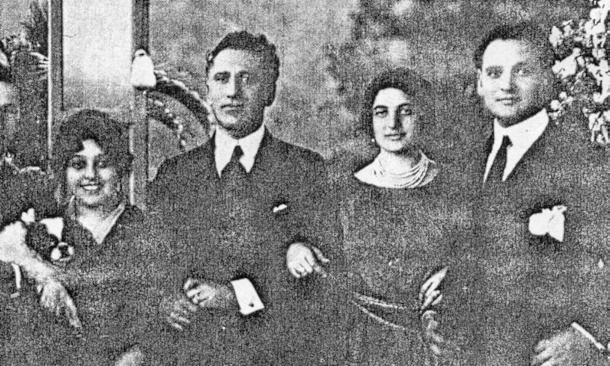

When the first Chicago season ended the Great War was convulsing Europe; fearing the dangers of crossing the Atlantic, Raisa and Rimini remained in the United States. In so doing, Raisa forfeited her announced engagement in Monte Carlo, where she was scheduled to create Magda in Puccini’s new opera, La Rondine. Instead, they rented a summer cottage in Asbury Park, New Jersey and enjoyed a long vacation. Both made their first, and not particularly successful, recordings for Pathé Fréres in New York City in the late spring. Staying in the same Asbury Park community were other opera luminaries such as Cleofonte Campanini and his wife Eva Tetrazzini, the Riccardo Stracciaris and Giovanni Zenatello and his wife Maria Gay (see picture above). An opera company was formed giving performances, starting in late August, in Mexico City at the Teatro Arbeu under Giorgio Polacco. Raisa, Rimini, Stracciari, Zenatello and Gay joined this enterprise. On the train ride to Mexico City the young José Mojica perceptively observed in his memoirs that Rimini was Raisa’s “sweetheart.” Rimini sang Iago in the 31 August opening night Otello with Zenatello and Anna Fitziu. He also sang in many Aidas with Raisa. The Mexico City season had barely ended when Rimini returned to Chicago to rehearse and then barnstorm eight Mid-Western cities in just over two weeks singing Enrico in Lucia with Galli-Curci, Crimi, and Vittorio Arimondi; Campanini conducting. The Lucias were every other night in a different city, and the in-between days were Fausts with Nellie Melba/Jesse Christian twice, Lucien Muratore, Alfred Mauguenot and Leon Rothier/Georges Baklanoff/Gustave Huberdeau; Campanini conducting all sixteen performances in a period of eighteen days. This small tour, featuring the great Melba and the new star Galli-Curci on alternate nights, should be remembered for bringing together the shining lights of their respective generations.

When the regular season in Chicago opened on 12 November Campanini presented the North American première of Mascagni’s Isabeau, with Raisa as Isabeau, the Lady Godiva character, Crimi as Falco and Rimini as King Raimondo. Isabeau was given four times in Chicago, twice more on the tour in New York and Boston. With the fame and pre-eminence of Galli-Curci, vehicles for her had to be unearthed, and on 16 November Rimini sang the first of five Hoëls in Meyerbeer’s Dinorah in Chicago, more on tour. However, the most significant new assumption for the young baritone was Rafaele in Ermano Wolf-Ferrari’s steamy melodrama I Gioielli della Madonna. This opera was essentially a Raisa vehicle and they gave it forty-four times over the next fifteen years at the Chicago Opera and on its tours. Rafaele is a picturesque role; the swaggering local “Mafia” chieftain has a lyrical serenade and some serious declamation. Clearly, this is the one opera that they ‘owned’.

It was in this opera that Raisa and Rimini were introduced to New York audiences on 24 January 1918 at the Lexington Opera House. The Brooklyn Eagle found Raisa to be “a big, full-throated voice of remarkable power and extraordinary purity of tone…of wide range…handled with great facility…The Rafaele was Rimini, also making his Manhattan debut. Here is a young Italian baritone with a voice of considerable natural beauty, but unfortunately the organ is not handled with any art. It is never focused properly and lacks any measure of head tones. His is the sort of singing that makes for an early vocal decay. As an actor he is more than effective and he has fine stage presence. On the whole his conception of the role was intelligent and satisfactory.” Herbert Peyser in Musical America found his voice “eminently pleasing and of serviceable quality.” This season both Georges Baklanoff and Riccardo Stracciari made their Chicago Opera debuts and therefore Rimini sang fewer of the glamorous roles than he had the previous season when he was the featured Italian baritone. In fact, Rimini, in his over sixteen consecutive years at the Chicago Opera, performed Rigoletto, probably the most coveted baritone role in all of Italian opera, only a handful of times, usually when Stracciari, Carlo Galeffi, Ruffo or Josef Schwarz were indisposed or in popular-priced Saturday evening performances. As the Company’s very dependable ‘cover’ artist he was often called upon, often at the last minute, to save performances. Over the years he sang with Raisa more than his fair share of Amonasros and Scarpias beyond the Falstaffs and Rafaeles. All operatic music is vocal—some roles more purely so than others. No soprano ever acted her way through ‘Ernani Involami’, any more than any baritone did through ‘Il Balen’. However, there are some operatic roles whose creation can be greatly helped by superior stage craft, skillful vocal nuance, and expressive handling of the text as much as by sheer voice. To these “singing actor” roles Rimini moved, whether by inclination or necessity.

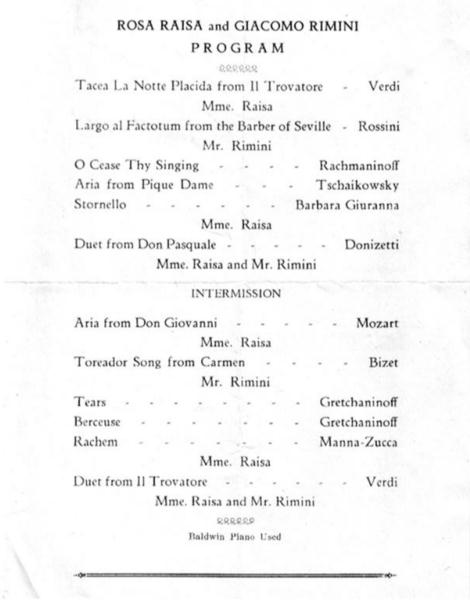

Raisa, this season, 1917-18, launched her American concert career and Rimini was almost always the assisting artist. Billed alphabetically as “Raisa and Rimini”, no distinction of rank was made in the marketing of their concerts. Having examined over a hundred of their concert programs it is fair to say that the formula was for Raisa to sing two-thirds of the programme and Rimini one-third; rarely did these proportions change. At the conclusion of both halves of the printed program they would sing duets. The Act IV Trovatore, Luisa Miller and Don Pasquale duets were staples of their concert repertoire and two of the duets most likely to be on the printed programme. All three duets gave opportunities for Raisa to show off her coloratura and end with applause-getting high notes. ‘Là ci darem la mano’ from Don Giovanni was one of their frequent encores. Over the years they sang every conceivable duet for their type of soprano and baritone, a veritable encyclopedia of the literature.

1918 in South America is the season in which Raisa sang her first ever Normas: seventeen times in all. Rimini performed Amonasro, Renato in Un Ballo in Maschera and Falstaff, for a total of twenty performances, all with Raisa as Aida, Amelia and Alice. Of more than cursory interest is that in this 1918 season Mariano Stabile was a member of this ensemble and he performed Ford to Rimini’s Falstaff in a cast that included, in addition to Raisa, Vallin, Matilde Blanco-Sadun and Charles Hackett, with Gino Marinuzzi at the helm. It is fascinating, because most people who know and study opera performing history assume that Stabile was always the Falstaff of choice between the wars, that he is considered by many the greatest Falstaff of all and that he is mentioned in the same breath as Maurel, Verdi’s choice to create the role. Today, we think of Falstaff as a role often, but not always, assigned to ageing baritones or bass-baritones because its vocal demands, while considerable, can be met halfway as long as the artist has commendable theatrical skills. His undertaking of Ford is remarkable as the role is often assigned to young baritones with fresh and powerful voices (adjectives rarely assigned to the Stabile voice) such as the twenty-eight year old Lawrence Tibbett at the Met. Stabile was only two months younger than Rimini (born 12 May 1888) when they performed together in Buenos Aires.

When the couple returned to the United States in early November the ‘Great War’ was about to end and many difficult wartime restraints were lifted. Rimini added Di Luna, Barnaba, Marcello, and Sharpless to his Chicago Opera role list; the Trovatore and Gioconda roles almost always with Raisa and the Sharpless this season to Japanese soprano Tamaki Miura, and in later seasons often to Edith Mason’s much admired Cio-Cio-San. The Musical Leader found his Di Luna “picturesque, statuesque, romantic, well-schooled and with an easy flow of tone.” In his reviews at this time opinions were divided about his vocal abilities; there was no equivocation about his superior stage craft.

In New York on the 1920 tour Rimini presented his Falstaff, and the New York critics did not value his portrayal as had the Italian and South American ones. The usually sound Herbert Peyser, writing in Musical America noted: “The Falstaff of Mr. Rimini was more credible in intention than memorable in result. Much of the music he sang better than anything he has ever done here. On the other hand one missed all trace of unctuousness. There was little fun in this fat knight’s enactment of the buck-basket episode, in his wooing and his final discomfiture, and the “Quand ero paggio” passed by almost unnoticed. Why is not the assistance and counsel of Victor Maurel, the Falstaffof Verdi’s own choosing, invoked by contemporary representatives of Sir John?” Peyser is letting us know both that he heard the great Maurel’s Falstaff many years before, and also that Maurel, who was living in straightened circumstances on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, was taking students. Months later when the tour arrived in California Raisa gave an interview to the San Francisco Call, and said: “You know Rimini was chosen by Toscanini to sing Falstaff and perhaps I should not say it—but indeed he is splendid in the part and his Tonio to Muratore’s Canio is comedy unsurpassed. I always stay in the wings to watch and I cannot keep from laughing at his drollery—it is so funny.”

In the summer of 1920 Raisa and Rimini for the first time in many years did not accept engagements in either South America or Mexico, but instead they took their vacation in Italy. Upon their return to the United States in late September they announced to the press that they had recently married outside Naples. They were now treated as Mr. and Mrs. Rimini, husband and wife, and much ink was spilled with a human interest slant about their recent marriage in both the musical and the non-musical journals. However, their lives were not to be without complication. While they had a full calendar of opera and concert bookings to honor, there were serious legal issues needing resolution. It appeared that their announced marriage was just that, an announcement; it had not actually taken place yet. In their minds their marriage was real as they had been both partners and lovers the past four years. But, there was no divorce in Italy, there was no civil marriage, and he was still married to his first wife. They needed a strategy to make their marriage possible. The legal ‘mechanism’ Rimini used was to go to the American courts in April 1920 showing the judge that a properly addressed support payment to his wife Delizia was returned by the postal authorities marked that the addressee was “not found”. The court ruled that his wife was presumed either dead or that she had abandoned their marriage, thus freeing Rimini to remarry, at least in the United States. This was only a pretext because Rimini, through his sister Zeplina in Milan, was in contact with his daughter Rafaelle, who surely knew where her mother Delizia could be found; this came back to haunt Raisa after Rimini passed away in 1952. On 10 November Raisa and Rimini married (well documented) in a civil ceremony in St. Joseph Michigan, a two and a half hour drive from Chicago. The low-profile November marriage did not raise embarrassing public questions as to what the September marriage announcement was all about. The press did report that the new couple was feted at a reception co-hosted by Mrs. Edith Rockefeller-McCormick and Mrs. Julius Rosenwald, both important patrons of the Chicago Opera and leaders in their respective society circles. Now they were truly Mr. and Mrs. Giacomo Rimini. (After Rimini died in 1952, without a will, there was a prolonged legal battle, well reported in the Chicago press, initiated by Rafaella Rimini Bettei who claimed she was entitled to her father’s entire estate as Rimini’s marriage to Raisa was never legal, as Rimini was legally married to Delizia and that the American court writ declaring their marriage over was clearly a subterfuge. The court entertained affidavits from friends of the Riminis to the effect that Rafaelle knew quite well that Raisa and Rimini were legally married as she had often lived with them for many months of many years both in Italy and Chicago. Giorgio Polacco was one of the attesters to this fact. In the end the court awarded Rafaelle one-third of the cash estate. Raisa and their daughter Jolly one-third each. Property assets, primarily the villa outside Verona, were already in Raisa’s name.)

Complicating their lives, with the marriage issue in the background and a full performing schedule, was the simultaneous arrival in the United States of Raisa’s father Herschel, stepmother Chaya, sister Frieda and brother Aron. Raisa had finally arranged to bring them to the United States from Bialystok, Poland after the Great War ended. She bought her father a house in New York and supported the family. As very traditional orthodox Jews of their generation and outlook they would not have been particularly hospitable to Raisa’s inter-marriage, but she had convinced her father that Rimini was “sort of Jewish”, having himself a Jewish father. Rimini was very skilful, integrating himself into Raisa’s Jewish family and circle of friends while maintaining his basic Italian identity. With his good ear for languages he picked up many Yiddish phrases and expressions and he showed proper respect for his father-in-law Herschel and the family’s customs. He participated in holidays such as Passover and he was always at Raisa’s side when she sang for Jewish charities and organizations. One of Raisa’s oft-told anecdotes was that her father, after a Gioconda performance, was quite upset that in the fourth act Rimini (Barnaba) raised her up, and dropped her on the stage floor in a manner that could have seriously injured her. Raisa’s explanation to him was that this was merely stage business, albeit well-rehearsed stage business; still her father felt that her husband should have found a less violent way to achieve the desired dramatic effect.

(Rimini-Raisa and her father)

(Rimini-Raisa and her father)

During the 1921 season in New York Raisa was criticized by some of the critics for her questionable vocal method and some going so far as to predict for her a shortened career. Perhaps realizing that even experienced artists can always improve, Raisa and Rimini retained Lazar Samoiloff, a former Russian tenor and now a highly publicized New York vocal coach, to work with them, hoping to firm up their voices and their reputations. As Samoiloff maintained a high profile as a vocal authority, advertising his studio and his roster of advanced students regularly in the music journals, everyone in the classical music business now knew they were working with him. On the assumption that he worked miracles, reviewers noticed all manner of good things happening to the couple and so reported these changes for the better in their reviews. One can fairly ascertain which critics moved in the same professional circles as Samoiloff. W. J. Henderson, the critic of the New York Sun, and a friend of Samoiloff, noted after a 1923 concert in New York that “the remarkable power and plentitude of it [Raisa’s voice] have gone through a beneficent process, and there is a refinement now in her use of it which gives its prodigious coloring the highlight of ease. Rimini too has rebuilt and cemented his voice considerably.”

(example of concert programme)

(example of concert programme)

After the Chicago tour Raisa and Rimini joined Impresario Walter Mocchi’s company touring South America. This company featured Raisa, Gilda Dalla Rizza, Gabriella Besanzoni and Gigli as the main stars; other famous singers being the emerging Toti dal Monte, Tamaki Miura, Augusta Concato, Fanny Anitua, Antonio Cortis, Angelo Minghetti, Carlo Rossi-Morelli and Giulio Cirino, all under Marinuzzi’s direction. This tour started in Brazil and worked down to Argentina and Uruguay, reversing the usual pattern of starting in Argentina and working north to Brazil. In the Brazilian portion of the tour the company offered Carlos Gomez’s opera Lo Schiavo; this Portuguese language opera was given in Italian, three times in Rio de Janeiro and twice São Paulo. Raisa sang Ilara, dal Monte: Condessa de Boissy, Minghetti: Americo and Rimini: Iberê. Other Rimini roles were Chim-Fen in Leoni’s L’Oracalo, Wolfram in Tannhäuser, Rigoletto, Tonio, Barnaba and Falstaff, and the Western Hemisphere première of Mascagni’s new opera Il Picolo Marat. The last five roles were performed only in the Argentine section of the tour. In the Mascagni opera Gigli assumed the title role, Dalla Rizza played Mariella and Rimini was Il Carpentiere. Rimini overall gave forty performances on this tour of three and a half months. The Mocchi company leased the Teatro Coliseo for the Buenos Aires portion of the tour. The Colón season was ending at the time Mocchi’s troupe came into the capital. The Colón season was equally glamorous as it showcased Claudia Muzio, Vallin, Barrientos, Luisa Bertana, Crimi, Martinelli, Galeffi and Adamo Didur under the direction of Panizza and Polacco. The combined artist list of both companies meant that Buenos Aires in 1921 witnessed many of the greatest stars of the Italian operatic world.

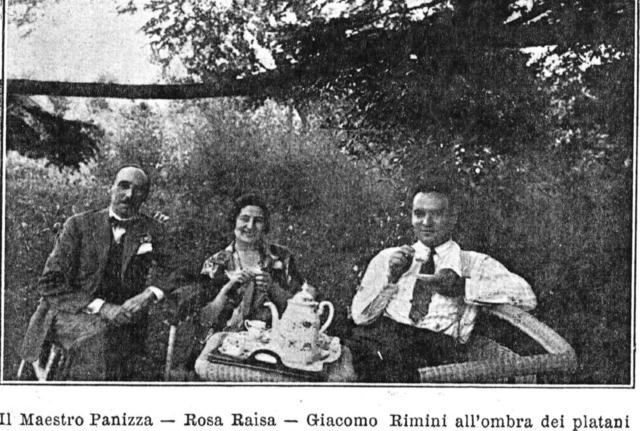

(Toti Dal Monte - Samiloff- Raisa-Rimini)

(Toti Dal Monte - Samiloff- Raisa-Rimini)

With his ability to work the media, Samoiloff in South America was himself treated as a celebrity and enjoyed being photographed with the opera stars. When he returned to New York the Musical Courier questioned him about the “work ethic” of the Riminis: of Raisa he said “She is the most diligent, conscientious artist I have ever seen…Rimini is a simple, good-hearted, companionable man, who works hard to enlarge his repertory. Toscanini said he was ‘one of the greatest artists on the stage.’ He leads a model life, temperate always in all things. His love of photography led him to buy four cameras, and he is looking for more. He, Franchetti [Samoiloff’s pianist] and I played checkers until I was black in the face, although the very poorest player.” Toscanini had been in New York in the winter of 1921 on a tour of the United States with his Scala orchestra and he went to some Chicago Opera performances at the Manhattan Opera House. He was planning the reopening of La Scala in December (La Scala had been closed since 1917). He invited Raisa for Norma and La Wally (he had last conducted Norma over twenty years ago) and he asked Rimini for the opening night Falstaff. These prestigious invitations were declined by the Riminis as they properly chose to honour their Chicago Opera contracts, even though there is evidence that they were not happy about the upcoming Mary Garden directorship of the company and the rumoured downgrading of Italian opera. Toscanini was never again to conduct Norma and Mariano Stabile instead was the Falstaff for the Maestro’s Scala 26 December 1921 opening night. It is intriguing contemplating that Toscanini, so involved with Verdi in the composer’s last years, and with an especial affection for Falstaff, thought so highly of Rimimi’s artistry in this role while the New York critics found him sadly wanting. The decision to remain with the Chicago Opera for Mary Garden’s 1921-1922 season was a decisive moment in their joint career. (Letter of A. Bollastri (artists’ agent) dated 30 July 1921 to Gatti-Casazza of the Metropolitan Opera. In this letter he conveys to Gatti that both Gigli and Raisa enjoyed huge successes in Rio de Janeiro. He indicates Raisa’s displeasure with plans for the upcoming Chicago season under Garden, and offers her services to the Met. Suggests that if they were interested in Raisa, Rimini would take whatever they felt they could offer him, realizing that it probably would not be much, if anything at all, since the Met was well staffed with baritones who sang his repertory.) Had they elected to abandon Chicago or reestablish themselves in Italy or take whatever the Metropolitan Opera could offer them, their careers may have developed quite differently, maybe better, maybe worse. In my judgment they made the correct decision.

At the Chicago Opera, as in other companies, the salary structure reveals the company’s hierarchy. In January 1921 business manager Herbert Johnson sent a document to Charles Dawes, Chairman of the executive committee, outlining the singer engagement/salary plans for the upcoming 1921-1922 season:

SALARY PER PERFORMANCE

Yvonne Gall $1,000 Gabriella Besanzoni 600

Galli-Curci Chicago 2,000 Sigrid Onegin (Option) 700*

New York 2,500 Alessandro Bonci 1,200

Other Tour 3,000 Edward Johnson 1,250

Mary Garden 2,500 Riccardo Martin 500

Florence Macbeth 250 Lucien Muratore 2,250

Rosa Raisa 1,600 Tito Schipa 1,800

Rosina Storchio 400* Charles Marshall 600

Edith Mason 500 Georges Baklanoff 750

Maria Ivogün 650 Carlo Galeffi 850*

Titta Ruffo 2,500*

SALARY WEEKLY

Margery Maxwell 150 Désire Defrère 250

Marie Claessens 175 Hector Dufranne 500

Joseph Hislop 700 Giacomo Rimini 1,200

Forest Lamont 500 Edouard Cotreuil 350

José Mojica 100 Virgilio Lazzari 400

This document is of the plan; The four artists with *s after their salaries did not perform in 1921-22. With the exception of Sigrid Onegin they had performed the previous season 1920-21.

In the 1921-22 season Raisa sang 42 times, suggesting that she made $67,200, and Rimini 20 weeks for $24,000, bringing their total Chicago Opera earnings for that season to a shade under $100,000, an awesome amount of money in that pre-high tax era. Rimini, by far, was the highest paid singer on ‘weekly’ status. Overall, during his seventeen seasons with the Chicago Opera, Rimini sang 466 times with the organization, of which 177 were on the national tours. With the Chicago Opera he sang with Raisa 185 times. Up until his last seasons he continued on weekly salary status.

(Mary Garden, director)

(Mary Garden, director)

When ‘Directa’ Mary Garden’s 1921-1922 season, with all its controversy and rumoured huge losses, came to a close the Chicago Opera reorganized itself as a civic enterprise and utility magnate Samuel Insull took the leadership reins; it was renamed the Chicago Civic Opera. From opening night 15 November 1922 with Raisa in Aida until its demise in February 1932 the Civic maintained its distinctive profile with a roster of singers, conductors and directors heard exclusively in America with the Chicago Opera, with only a few exceptions (primarily Chaliapin in 1922-1924). Raisa and Rimini were engaged every year with salary increases; Raisa’s salary may have been even more, but it reflected the generous terms of Rimini’s weekly salary.

In the summer of 1922 the Riminis purchased a villa in the town of San Floriano, a few miles west of Verona; they modernized it and often played host during the summers to their American and Italian friends, many from the opera world. Generous hospitality was a given. Rimini was a born ‘tinkerer’ and collector of gadgets of all kinds; he had a passion for photography, recording devices, automobiles and anything electrical. It is a pity that most of his photographs and none of his private recordings were preserved, to my almost certain knowledge. He also had a passion for speed driving, and in a 1917 newspaper clipping there is reference to his being arrested in New Jersey for going almost twenty miles over the speed limit, and a 1924 magazine dispatch from Milan refers to an automobile race from Lake Como to Milan in which he was involved in a competition with the new premier of Italy Benito Mussolini. He lost the race as he smilingly claimed Mussolini had “the better car.”

During the next ten years (1922-1932) of the Insull era at the Chicago Civic, Rimini virtually owned certain roles (Figaro, Sharpless, Marcello, Rafaele, Falstaff, Malatesta and Belcore), and he added new roles in revivals in rarely given works (for example Pearl Fishers, Iris and Tiefland). When a baritone with a greater voice or reputation joined the company Rimini’s place in the pecking order was accordingly lowered as the new star baritone was integrated into the Company. First Baklanoff in 1917, and later Cesare Formichi in 1922, joined the Company and appropriated the roles ideally requiring a heavier voice. The great Latvian baritone Joseph Schwarz in 1921, in addition to some German roles, sang Iago, Germont, and Rigoletto. The Italian baritones Luigi Montesanto and Giovanni Inghilleri, the Catalan Vincente Ballester and Uruguayan Victor Damiani at various times sang seasons in Chicago and performed roles that were part of Rimini’s oeuvre. And the American baritones Richard Bonelli and John Charles Thomas would carve out leading positions. During this period Raisa’s place in the company flourished, and after Galli-Curci left for the Metropolitan (at first part-time in 1921-22 and finally in 1924) she became, other than Mary Garden, the highest paid female singer on the roster. In late 1922 Claudia Muzio joined the company and, although she was clearly a rival of Raisa (at least in both their minds), Rimini was very often cast with Muzio. On 23 November 1924 the company presented Aida twice the same day, demonstrating their casting depth:

Matinee: Raisa, Lenska; Marshall, Formichi, Lazzari. Polacco

Evening: Muzio, Van Gordon; Lamont, Rimini, Cotreuil. Moranzoni

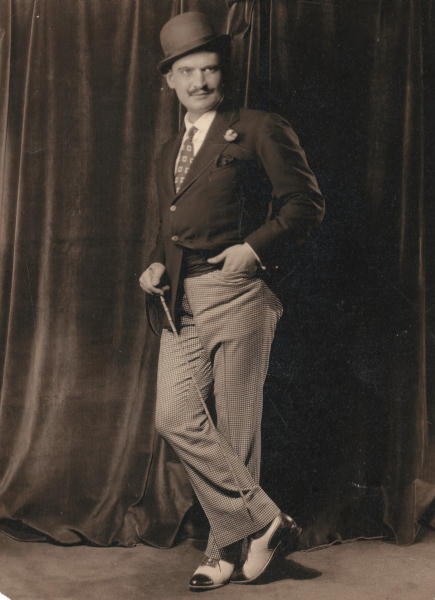

In 1922 Rimini added Jack Rance in Fanciulla del West to his Chicago repertory; the company took this opera to New York and Pitts Sanborn in the Globe remarked, “Rimini wore in lifelike fashion the sinister weeds of Sheriff Rance, and Rance is a fellow that the costume practically makes. In the first act his quiet was eloquent; in the second he stepped out as a heavy-footed villain of age-old melodrama, a frontier Scarpia balked of his prey by her stockinged ace.” In a performance of Figaro in Barbiere (1924) Karleton Hackett, who seven years previously had been so doubtful of his potential, happily noted, “Rimini gave a spirited performance and looked as if he might have had every social strand of Seville in his hand and have known just what to do with them. He had the comedy vein and sang the best I ever hear him. The tone was lighter and brighter without the heavy, somber quality, and he skipped through his scales cleverly. Would that he would do this sort of thing more often.” This praise must have been a tonic for his ego because some of the internal discords within the Company re roster and casting which spilled into the public prints involved himself. The Chicago Tribune (1924) printed this letter to the editor: “Repeatedly the beautiful operas are utterly ruined by a certain baritone, who has no voice at all, cannot sing on pitch, and while he may act and dress the part, that is not what we pay for. Opera requires a singing voice, not so much the dress and acting. A number of subscribers have canceled their subscriptions because they drew this supposed baritone so often on their night in years past. If box office receipts are worth considering, it would be wise to keep this artist (?) off the cast. Pay him his salary if he has to be kept on the payroll, but give the public a chance to enjoy opera—Subscriber.”

In the autumn of 1925 the Company’s customary and charismatic Escamillo, Georges Baklanoff, was winding down his Chicago career and a new toreador was needed. Carmen at the Chicago Opera in this period was a Mary Garden property and Rimini was given the assignment. He also did service as Manfredo in L’amore dei tre re, an Italian opera she sang in French. Perhaps a predictor of these new roles was his participation on the 1924 tour when in Los Angeles he replaced Baklanoff as Marc Antoine in Massenet’s Cléopatre, yet one more Garden French vehicle. One is fairly certain that Garden probably had veto power over who would be the associate artists in “her” operas, and therefore Rimini’s selection tells us much about his suitability for these assignments. Montesanto, Vanni-Marcoux and Kipnis also sang Escamillo in this period.

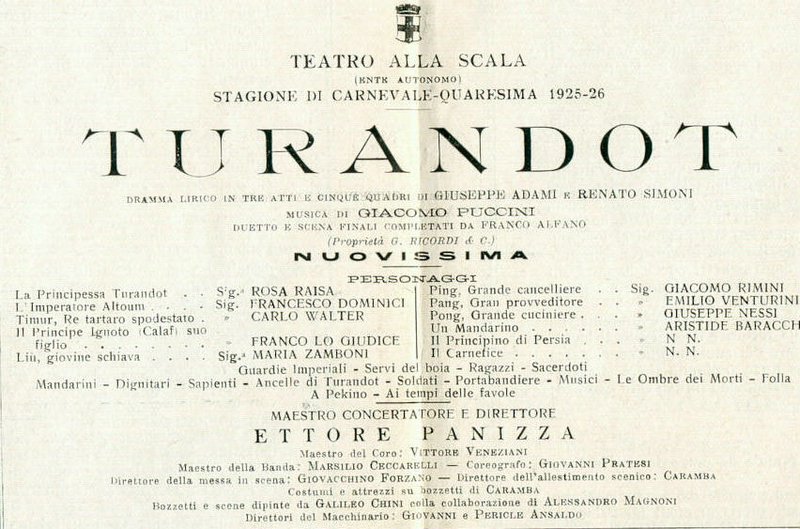

Rimini accompanied his wife to La Scala in her three seasons, 1924, 1925 and 1926 (world premières of Nerone and Turandot, and a new production of Il Trovatore), and in 1925 Toscanini cast him in Falstaff, which he repeated in 1926. The performance on 25 April 1925 was in honour of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the coronation of the King of Italy. “The boxes were filled to overflowing with all Milan’s aristocracy, magnificently gowned and wearing many jewels. The house was filled to capacity in spite of the triple price for seats for this performance.” The Musical Courier Milanese correspondent Antonio Bassi wired: “Giacomo Rimini in the name role achieved a phenomenal success especially with his Monologue. He was brought back to the stage many times in response to the thunderous applause. The press commented especially on his splendid voice, his exquisite and rare interpretation, and called him a great singer.” When Raisa was selected by both Puccini and Toscanini for the creation of Turandot, Rimini was also cast as Ping, a relatively small part, but still the lead baritone role.

In the 1926 Turandot season, he repeated his Falstaff, but this time under Panizza, replacing Toscanini who had suffered a nervous breakdown from overwork and had exited from conducting after the third performance of Turandot.

(note: Miguel Fleta, like Toscanini, only participated in the first 3 performances; Franco lo Giudice sang the remaining 5 Calafs of the initial Scala run)

Rimini’s career, on a parallel track with that of his wife, sputtered as she struggled the next five years to bear their child. Cancellations, withdrawals, and refusals of prestigious offers occurred in the 1927-1931 period. Although both artists enjoyed great nights at the Chicago Opera and at the Buenos Aires Colón in 1929, this was the period which also saw the “roaring twenties” peak and then collapse with the stock market crash that year, ushering in the world-wide depression. The Riminis were almost the perfect models of this era and its fall, having acquired a fortune of a million dollars on paper, only to be “wiped out” when their holdings of Insull stock became virtually worthless.

Little Rosa Giulietta Frieda Rimini made her debut on 7 July 1931. The baby was named for Raisa, Rimini’s mother Giulia and Raisa’s mother Frieda. As Raisa’s career moved irregularly the previous five years to accommodate six miscarriages, and now with the added loss of their fortune, Rimini began to accept more work in Europe, where he was valued as an important artist, even more so than in Chicago, where his status depended heavily on Raisa. In the autumn of 1928, when it appeared that Raisa would not return to Chicago for the season due to a difficult, ultimately unsuccessful pregnancy, Rimini went to Bologna (the Communale) for a run of Otello with Maria Laurenti and Renato Zanelli. Engagements of this level of would be his undertakings for the next several years until he finally officially retired in 1937.

(Rimini,Raisa, baby Giulietta and Rafaella his daughter from his previous marriage)

(Rimini,Raisa, baby Giulietta and Rafaella his daughter from his previous marriage)

In 1932, late April, early May, Rimini recorded his Falstaff for Columbia (EMI) in Milan. In the original plan Raisa was to sing Alice, but she was again having a difficult pregnancy and too ill to make the recording. She lost a baby boy a few months later. Pia Tassinari, at the beginning of her career, was her replacement. In 1983, when I interviewed their daughter Jolly, she told me (presumably family lore) that Toscanini was upset that Raisa was not able to sing her Alice on the complete recording. In pondering this information I thought that perhaps all the rumours I had heard over the years in record collecting circles that the mysterious Lorenzo Molajoli never existed and the name was merely a pseudonym for Toscanini himself, were perhaps true. Otherwise, why would Toscanini care who sang the Alice on this recording unless he thought so much of Raisa’s Alice, which she sang for him at La Scala, that he regretted it was not preserved for posterity? This intrigued me. The best way to assess this kind of information is to determine where Toscanini was physically on the recording dates. The recording was made over a two week period from 30 March to 15 April, 1932. According to Harvey Sach’s encyclopedic biography Toscanini did not conduct from late January to late April 1932 due to a painful cure he underwent for a serious shoulder infirmity. Since that 1983 interview with Jolly, more information has been uncovered about the enigmatic Malajoli; he really existed and was one of the in-house Columbia Records studio conductors.

As noted previously Rimini was a very busy artist, mostly in Italy, in the early thirties. In 1933 Raisa, for the last time in her career, spent significant time in Europe and accepted a number of top level engagements; among them Tosca in both London and Berlin. Rimini’s role in these cities would be more extensive. In Don Carlos with Gina Cigna, Nina Giani, Ulysses Lappas and Fernando Autori (Phillip) Rimini made his Covent Garden debut as Rodrigo. The Musical Times wrote that “Rimini (Rodrigo) sang better after he had been shot in the last Act than at any other period. Perhaps a little blood-letting is good for grand opera singers, for Valentine [in Faust] invariably dies with his voice in its fullest bloom. A curious singer this Rimini. Small voiced, and seemingly out of place in the world of opera, his high notes sounded as if they went through a sudden process of inversion; they seemed shy of showing themselves. They went in instead of coming out, and eventually reached the listener in the form of tremolo. Rimini had the will to be an artist, but his effects were constantly misplaced, and his vowel sounds lacking in variety, owing to an insufficient interplay of tongue, lips, and teeth.” Not a review to quote in one’s promotional pieces! Of his Iago in Otello with Rosetta Pampanini and Lauritz Melchior the same monthly magazine noted: “Rimini was more in the skin of Iago than in that of Rodrigo, and it could not be fairly said that he let the performance down. His tremolo and vocal mannerisms were still there. You can not shed bad habits in a night. ‘Era la notte’ was nearly first-rate. So long as Rimini kept to a conversational style and worked his will through the means of an unforced and implied deviltry, he was by no means ineffective in his role of gad-fly.”

In October 1933 in Berlin at the Städtische Oper there was a one-week rather controversial stagione of visiting Scala singers that featured Gigli, the Riminis, Arangi-Lombardi, dal Monte and Ebe Stignani under Panizza. It was controversial due to the Jewish Raisa’s participation, and even Rimini’s half-Jewish ‘racial’ status.

(caricature from a Berlin newspaper)

(caricature from a Berlin newspaper)

True, the Nazis at this time had only been in power nine months. Herbert Peyser, who a decade earlier had been equivocal about Raisa and mostly negative about Rimini in their New York performances with the Chicago Opera, had second thoughts about both artists. He thought Raisa’s Tosca magnificent and one for the ages. In his Musical Courier review of the 8 October Aida he said that Arangi-Lombardi was “uneven” and Stignani only rising slightly over a “dead level of mediocrity.” But “as it was the performance moved in rather provincial ways until the second act Mr. Rimini burst upon the scene. Never have I appreciated the artistry of this baritone as much as during these Berlin performances. Has my own judgment been at fault or am I right in harbouring the dark suspicion that the man has become a much bigger artist than he was? At all events he dominated the stage from the moment he set foot on it and diminished the others by the thrust of his own presence and personality. I shall not deny that his top tones show signs of honourable service but an Amonasro who can sustain his share of the Nile scene with such dramatic vigour and driving power is a pretty serious matter. Yet Aida was only the first of his imposing achievements in Berlin. Mr. Rimini presented a commanding Enrico Ashton two nights later in Lucia. And a couple of days after that he revealed his blithe and mercurial Figaro, in the Barber of Seville—a Figaro I have barely seen surpassed since the days of the beloved Giuseppe Campanari.” Strange that Rimini sounded so major in Berlin and so minor in London, only four months apart. Could the relative size of these two opera houses been determinant? Or is this impression one of those enigmas that defies rational explanation, a sort of “you had to be there to know” occurrence?

Although Rimini’s Figaro was a new and surprising revelation to Peyser, Chicago critics had considered him definitive in this role for many years. Hackett in 1925 thought that “It is his best role and he sang it with comprehension of the music and the lighter more highly colored tone which he reserves for this part.” In 1930, in the new Civic Opera House, the Musical Courier noted: “we must sing the praise of Giacomo Rimini, who sang the title role. His Figaro is an old acquaintance and he has been much admired in the part since he first made it known to us, but in all these years he has added here and there some details in his portrayal and as he is more resourceful vocally today than yesterday his Figaro now stands out as a cameo carved with intelligence and understanding.” In Chicago Galli-Curci, Graziella Pareto, dal Monte, de Hidalgo and Margherita Salvi were some of his outstanding Rosinas. Tito Schipa and Charles Hackett were often his Almavivas, and Lazzari his most frequent Basilio; however in 1923 and 1924 the gigantic Chaliapin was the music master. Vittorio Trevisan, Chicago’s resident basso buffo, was invariably the Doctor Bartolo.

Even though Raisa returned from Europe to the newly-constituted Chicago City Opera (December 1933) after the early 1932 collapse of the Insull Chicago Civic Opera, Rimini remained in Italy and appended a notable coda to his career with performances of his best roles: Falstaff, Rance, Scarpia, Iago, Gianni Schicchi and Barnaba. And he added Boris, Don Pasquale, and Don Giovanni to his large repertory list. Castlemaggiore, Viareggio, Ferrara, Pesaro, Montecatini, Novara, Capri, Rimini (1932, Vittorio Emmanuele, Tosca with Raisa and Gigli) Piacenza, Treviso, Forli, Faenza, Vicenza, Macerata and Bergamo (1936, Fanciulla with Dalla Rizza) were added to his performance cities, and there were important return engagements to La Scala (1933), the San Carlo, Naples (1932), Rome (1933, Reale, Tosca with Muzio and Gigli), Genoa (Carlo Felice, 1933), Bologna (1932, November 1935 Mascagni’s Nerone under the baton of the composer), Modena (1932, Boris), Verona Arena (1933, Gli Ugonotti), Venice (1934, Boris and Scarpia and 1935), Florence (1933, May Festival, Falstaff), Trieste (1935, Don Giovanni under Hermann Scherchen). He also made guest appearances in London (1933, Covent Garden, Rodrigo and Iago), Berlin (Städtische Oper, Figaro, Amonasro, and Enrico), Budapest (1934, Falstaff and Iago) and Madrid (1936, Teatro Zarzuela, Scarpia and Marcello). In 1936 he tried his management skills as impresario of the “Stagione Lirica Carnevale” at the Regio in Parma and while there he returned to his role Giovanni in Francesca da Rimini. In this non-Chicago Opera phase of Rimini’s career he had the opportunity to sing with many of the operatic luminaries of Italy. Having sung mostly with his wife during his prime and the centre portion of his career he must have found it comparatively interesting to both sing with and mentally compare these artists to Raisa. Of course, we are not privy to his thoughts. Some of these sopranos include Maria Caniglia, Gina Cigna, Giannina Arangi-Lombardi, Bianca Scacciati, Lina Bruna-Rasa and Vera Amerighi-Rutili, among the dramatics, and Rosetta Pampanini, Sara Scuderi and Margherita Carosio among the lyrics. And he had the luxury of singing with many of the great inter-war tenors; Dino Borgioli, Melchior, Lauri-Volpi, Francesco Merli, Galliano Masini, Paolo Civil, Alessandro Granda, Antonio Melandri and Nino Ederle. If one adds the above illustrious names to the list from his big career, he sang at some point with most of the important singers of his generation.

Raisa divided her time between the United States and her San Floriano villa, where she and Rimini were raising their daughter Giulietta (nickname Jolly). Rimini returned to Chicago for the short 1936-37 season, and in late 1937 Raisa and Rimini officially retired. They launched the Raisa-Rimini School of Singing, first at their suite in the Congress Hotel, their Chicago residence since 1916 and later on North Michigan Avenue. This venture was successful as their fame attracted many aspiring singers seeking their guidance; and in 1938 they took several of their students to Verona for additional study. Of the two now-retired singers, Rimini was probably the more intellectually and technically prepared and grounded as a teacher. Jolly told me that the baritone Rimini most admired was Stracciari, not Ruffo. I had assumed that Ruffo would be his baritone idol as he not only knew Ruffo’s singing and acting skills but also because they were social friends. This admiration was based on Stracciari’s command of dynamics, the ability to sing piano as well as forte. Raisa and Rimini did not go to Italy in the summer of 1939 because of the tense international situation; they returned to their Italian villa in 1946. In the later part of the war the Germans occupied northern Italy and they appropriated the Rimini’s villa (Giacorosa) for use as a communications outpost. In Chicago they enrolled Jolly in the prestigious Girl’s Latin School. Rimini made a few appearances after his retirement from the stage, singing some Bartolos in Barbiere with his students at the summer outdoor Grant Park concerts (1942 and 1943) and even Geronimo in Cimarosa’s Il Matrimonio Segreto in a 1947 staged performance at Chicago’s Civic Theatre with Giorgio Tozzi as Count Robinson. Tozzi, his most famous student, related that in Rimini’s teaching the emphasis was always on a beautiful and strong legato and clear enunciation.

On a personal level Rimini could be both abrasive and charming, and as he was a born raconteur he was very social, great fun at parties. Raisa in private life was very traditional, believing in that era’s conventionally accepted roles for husband and wife. This meant that Rimini controlled the family finances. He followed the markets and made occasional investment decisions. As he was the one who balanced the accounts he could be very unforgiving when Raisa went on one of her periodic shopping sprees. The fact that whatever wealth they had accumulated was largely a result of her star status was never an issue. He was the one who persuaded their family butcher to release prime cuts of beef during the strict meat rationing of World War II, when they were hosting a dinner for the visiting Toscanini. If children can be said to play favourites, then Jolly favoured Rimini over her mother. He indulged her and often gave into her wishes. He was the ‘good guy’ and Raisa the disciplinarian. In 1940, with the war clouds hanging in Europe and anti-Semitism in the air, it was at his insistence that Jolly was formally given her Catholic faith. Rimini understandably did not want Jolly to endure the prejudice and hardships that Raisa had encountered. Raisa was very broadminded about religious issues and agreed to this arrangement. It must be said that Raisa was madly in love with Rimini; she told trusted friends, sometimes with graphic detail, that she sang her best after great sex with Rimini. Even when Rimini strayed (he had a lecherous streak) Raisa forgave him. She had a remarkable sensitivity to and appreciation of how difficult it must have been for him to be the husband of a popular prima donna. Jolly told me that, when growing up, she remembered very often Rimini reminding Raisa that “although your star shines brighter, I am still the sun and you are only the moon.” In his last years Rimini suffered from severe diabetes.

(Jolly's wedding : students surrounding Raisa-Carol Longone-Martinellli-Lina (Rimini's sister) and Rimini)

(Jolly's wedding : students surrounding Raisa-Carol Longone-Martinellli-Lina (Rimini's sister) and Rimini)

When he died in his sleep in March 1952 Raisa recalled that it was Toscanini who was the first to telegraph her his deep condolences, and it was Polacco who flew to Chicago for his funeral. Rimini was later buried in the municipal cemetery in Verona, along side his mother Giulia (1913). Now Jolly (1990) and her husband, Doctor Charles Segala (1980) are buried as a family unit. It was Raisa’s last wish to be buried next to him in the family’s plot. Jolly elected not to send her body to Verona. Jolly’s daughter, Suzy, told me that she very clearly remembers Raisa living with their family in California in the last six years of her life, that she had a beautifully framed portrait of Rimini on her desk and every day she placed fresh flowers next to his picture. Theirs was one of opera’s great love stories.

(Raisa and Rimini in 1950)

(This biography first appeared in The Record Collector, for acknowledgements see discography article, for the magazine see our links)