Pechkovsky as Don José Portrait

FORGOTTEN TENOR STAR NIKOLAI K. PECHKOVSKY (1896 - 1966)

By Charles Mintzer

Pechkovsky as Don José Portrait

A In 1990 shortly after I retired from government service I placed a small advertisement in New York’s Russian-language newspaper Novoye Russkoye Slovo asking for persons with autographed opera singer materials for sale to contact me. I received many phone calls from Russians, many who had various books with photos of Chaliapin, not exactly what I was seeking; no satisfactory responses for the kind of autographed photos that interested me. A few weeks later I received a phone call from Vladimir Gurvich, who had heard about my request through a friend and thought he might have photos and autographs that would be of interest. So, we set up an appointment at his home.

Gurvich was from Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) but he had immigrated to the United States seventeen years earlier and was now a successful computer consultant. He had an amazing collection of autographed and unsigned photos of pre-1917 Revolution artists, both Russians and non-Russians, mostly Italians, who sang in his home city, and many from the Soviet period, mostly names that didn’t mean anything to me at that time. We liked each other and talked for hours about my interest in Russian and Italian singers. I asked Vladimir for his “evaluation” of the two very famous Russian tenors Sergei Lemeshev and Ivan Kozlovsky, well known in the West from their recordings. I was in effect asking for the Russian equivalent of the then popular Domingo and Pavarotti comparison that even non-opera lovers were asking me at that time at my office. This was the time of the “three tenors” phenomenon. He had an appropriate appreciation of both legendary Russian tenors, but told me that in Leningrad the tenor who was most appreciated and worshiped was Nikolai Pechkovsky. And I had never even heard of him. Vladimir explained that the Soviets had “written him out” of official accounts of opera history. Why? There was a big problem; Pechkovsky had been accused of siding with the Germans during the siege of Leningrad, and for that crime, after the war, he was arrested as a collaborator; also he was gay. Unlike Lemeshev and Kozlovsky, Pechkovsky was a dramatic tenor and his great role was Hermann in “Pique Dame,” the Tchaikovsky opera so beloved by the Russians. Gurvich told me that for many years after the war it was not correct to either own or play his recordings; neighbors could or would report you to the authorities, and this in Stalin’s USSR might lead to unpleasant consequences. The Soviet system in Pechkovsky’s time brooked no dissidence; books on opera and music crudely censored the mere mention of those persons anathema to the regime. The deluxe 1976 photo history of the Moscow Bolshoi totally leaves out the very important soprano star, Galina Vishnevskaya, who left the Soviet Union in 1974. There are no photos of her in this photo historical survey, and the reproduction of the program for the 1959 Bolshoi premiere of “War and Peace” has a smudge over her name, thus making it indecipherable. In earlier Bolshoi books she is given appropriate prominence. Mere mortals like Vishnevskaya and Pechkovsky could be “air brushed” out of Russian and Soviet music history, but they were not able to omit the great Feodor Chaliapin. He was too big a name and so central to Russian music history, known by all Russians as their greatest artist. Whatever reservations the regime had about his leaving Russia in 1922, his central place in Russian musical history was assured and could not be erased.

Gurvich passed away more than ten years ago. When writing this article I needed to “fact check” my Pechkovsky information very carefully as when one writes about wartime collaboration and sexual orientation one must be as accurate as possible as these can be very serious allegations. I spoke with the Russian Chaliapin expert Joseph Stremlin ***who lived in Leningrad during the time when Pechkovsky’s “post Gulag” situation was an issue. In this process I learned not only about Pechkovsky’s difficulties, but also about how the Soviet system worked, good and bad.

The facts are that Pechkovsky had a dacha (country home) in Kartashevskaya about 40 miles south of Leningrad. In the summer of 1941 the German army had surrounded Leningrad, but it was still possible for passenger trains to go outside the city for normal civilian travel. Pechkovsky’s mother had been living at his dacha and was very ill. So ill, in fact, that she was on a stretcher and could not be sent to Leningrad except by an ambulance-type of conveyance that was not available. Pechkovsky wanted to take her to Leningrad for more sophisticated medical care. (It is interesting that at this very time the Kirov was in the process of moving east as far as the city of Perm in the south Ural Mountains in order to maintain the Company under wartime conditions). In mid August 1941 the Germans cut the railroad line from Kartashevskaya to Leningrad and Pechkovsky was stranded behind the enemy lines. His mother did not get her needed medical treatment, and Pechkovsky now had to earn money. How does one obtain money? Usually by selling off possessions or working, and Pechkovsky’s marketable skill was singing. He worked (sang) in clubs patronized by Russians and educated Germans in the military who either knew, or learned of, his celebrity and also loved classical vocal music. During the war he also sang in clubs in the Baltic States, but there is no evidence he sang in Germany as some alleged. After the war he quite naturally wanted to return to the motherland, so he voluntarily turned himself in to the Soviet authorities. He was flown to Moscow and was arrested; on 12 November 1945 he was sentenced to ten years imprisonment by a special commission (not a jury trial). The Gulag camp to which he was sent was in the Arctic Circle. Although his treatment was not as harsh as that for most other prisoners, it was still a prison camp in one of the coldest regions and general conditions were very severe. He served his full ten years. As to the general belief that Pechkovsky was gay there were varying opinions. A prominent Soviet mezzo-soprano told Stremlin that she was fairly certain he was gay. Although Pechkovsky married one of his avid female admirers after his release from prison, her son Ilya, from a previous marriage, took his stepfather’s name. This sensitive issue is only explored as in Gurvich’s opinion his sexual orientation was almost as important in a negative way as was his alleged collaboration. Stremlin feels that Gurvich’s notion that it was dangerous to own or play Pechkovsky’s records as a certain path to trouble is a bit of an exaggeration.

A free man in 1956 Pechkovsky was allowed to work in some of the lesser opera houses (Sverdlosk, Riga, etc.) Although the Soviets “rehabilitated” him, as opposed to “exonerated” him, this involved returning to him his title of “People’s Artist of the Russian Federation” and even more important his “Lenin Order,” the highest honor in the Soviet Union (equivalent to the Congressional Medal of honor in the USA or the Legion of Honor in France). He was also provided with a decent apartment not far from the Kirov, but nevertheless he was not allowed to sing at the Bolshoi or the Kirov. In 1958 he secured work at the House of Culture in Leningrad, an amateur opera chorus collective. By this time Pechkovsky was a sixty-year old tenor, so realistically he could not re-establish his stellar career or his former glory. He sang a Hermann in “Pique Dame” with some of his students in 1965, a year before he died. He did sing two concerts in Leningrad in 1965, and the reports of that event have the theater packed to the rafters, seats on the stage, and pandemonium for the former beloved star. Stremlin at the time heard about the frenzied atmosphere at these concerts.

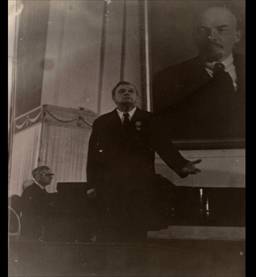

1965 Leningrad Concert, Pechkovsky wearing his Soviet honors

Some background about the social and political milieu in 1941 Leningrad: After the German attack on the Soviet Union the order immediately went out from Moscow to move all national treasures such as the most important art in the Hermitage museum, the Leningrad Symphony and the Kirov to safer locations far east in the Urals (Perm and Novosibirsk). The Hermitage already had in its basement appropriate containers needed to save and remove its masterpieces in the event of any calamity. The Kirov personnel and opera and ballet productions, (scenery and props) were loaded on trains and the Company was re-assembled in the city of Perm. Almost all the major artists relocated; those that did not had no established opera house in Leningrad in which to perform, so basically these artists worked by entertaining the public and especially the army in whatever venues could be found. The army had more generous food allocations than the general public in this time of great shortages; therefore the artists who performed for the army were relatively better fed during the siege. The great alto star of the Kirov, Sophia Preobrazhanskaya elected to remain in Leningrad. We can only speculate what Pechkovsky would have done if he had been allowed to return in 1941, and also wonder if his ailing mother would receive better medical treatment in the besieged city with its overworked hospitals and limited supplies? It is assumed that his mother died in Kartashevskaya because Pechkovsky was allowed after his “rehabilitation” to bury her remains in a Leningrad cemetery.

The importance of Pechkovsky: The very prominent St. Petersburg/Leningrad opera historian Sergei Levik in Volume II of his 1969 memoirs (yet to be translated in English) says that “in 1937 Pazovsky was conducting the dress rehearsal of “Carmen.” His choice for Don José was Nelepp. In the audience there was “top society, critics, singers, etc.” Nelepp sang well but nobody was really excited. Before the last act he suddenly got sick and was replaced by Pechkovsky. As soon as Pechkovsky sang his first phrase: “Je ne menace pas, j’implore, je supplie!” it was a feeling like some sort of “fluid” has penetrated into the audience. Some people even started spontaneous applause.” (pages 372-373.) About his Hermann, Levik concludes “One can judge him as one wishes, but one could never accuse him of falsity or pretense.” (page 374). This last phrase suggests to me that the merits of Pechkovsky’s voice and art were a subject of lively debate, that perhaps he was not universally adored, although mostly admired. The rivalry between Nelepp and Pechkovsky is a theme that still exists. On YouTube the few Pechkovsky selections are framed as Nelepp’s great rival.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OohPSBc4bTU

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UtkXHVzUvpM

Herman's ariaso, see soundbites

Herman in “Pique Dame” Don José in “Carmen”

Tartar-Persian mezzo Fatima MUKTAROVA was Leningrad’s favorite Carmen during Pechkovsky’s days at the Kirov (photo with the tenor in act 4 of Carmen and as Carmen close up)

Stremlin feels that although Pechkovsky obviously had a great voice, it was his acting ability combined with the great voice that made him so very special. You can sense his charisma in his photographs. Stemlin said that “After Stanislavsky had seen him in drama performances, he realized his talent and invited him into his Opera Studio, where Pechkovsky studied under his tutelage for about two years. Due to financial problems the studio was closed.” To give a sense of the love the Leningrad public had for Pechkovsky, Stremlin relates an anecdote that Giorgi Nelepp, the dramatic tenor, who was later to be a big star at the Moscow Bolshoi, once replaced Pechkovsky at a performance, probably Hermann in “Pique Dame,” and a goodly portion of the audience returned their tickets requesting reimbursement. Not much different from the “Carmen” incident Levik recounts.

This quick summary of Pechkovsky’s career is taken from the Kutsch-Riemens biography (on Operissimo.com), roughly translated (google) from German. Kutsch-Riemens is a body of work that is fairly accurate in describing the general contour of a career, although some of their specifics are erroneous: He was born in 1896. “He began his stage career in 1914 as an actor in the troupe of impresario Sergiewsky in the Moscow People's Theatre, came to the Narodny Dom (Public Theater) in St. Petersburg, where he decided to try his talents in a singing career. First, he believed, to have a baritone voice, but he was retrained by the tenor Lavrenty Donskoy in St. Petersburg for the tenor “fach.” He made his debut as a tenor in that vocal category in 1918, again at the Narodny Dom [Moscow], as Andrei in “Mazeppa” by Tchaikovsky. During the turmoil of the Civil War, he sang to soldiers of the Red Army. In 1920 he was on the recommendation of the People's Commissar for Education and Culture at the Bolshoi Theater Lunacharsky signed up in Moscow, where he presented in 1921 as his first role, Andrei Khovansky in “Khovantchina” by Mussorgsky, then the Lenski in “Eugene Onegin.” He appeared after the Nemirovich-Danchenko Theatre in Moscow and 1923 at the Opera House of Odessa (Hermann in “Pique Dame” with Marie Litvinenko-Volgemut) which was followed in 1923 by an engagement at the Opera House of Leningrad. (Maryiinsky/Kirov). Here, his career reached its apex, the opera public of this city celebrated him in a way scarcely to be described, which was at that time and under the conditions all the more astonishing. His big roles were next to Hermann in “Pique Dame” (his particular star role), the Romeo in “Romeo et Juliette” by Gounod, Don José in “Carmen,” Alfredo in “La Traviata,” Manrico in “Il Trovatore,” Canio in “Pagliacci,” Dmitri in “Boris Godunov” and later, Otello by Verdi. His eccentric appearance in public caused no less attention than his evocative, compelling presentation of art on stage.” The Kutsch-Riemens entry states that a complete “Pique Dame” with Pechkovsky was issued by Melodia Records. I have tried to locate this recording to no avail. Stremlin says this so-called recording does not exist. It is believed that a complete “Otello” was recorded by the Soviet broadcast system, but this single copy was destroyed due to Pechkovsky’s arrest.

With Lemeshev

Pechkovsky’s eminence in Leningrad highlights the fact that in Soviet Russia, as in Czarist Russia, and even somewhat today, the operatic worlds of Leningrad/St. Petersburg and Moscow were entirely separate entities and only on occasion crossed over. Lemeshev, Kozlovsky, Reizen and the other big stars of the Moscow Bolshoi seldom appeared in Leningrad in either concert or opera. Pechkovsky in his great days (the 1930s) before the war was not associated with the Bolshoi in Moscow. Both cities had their own artists and their own outlook on the world. Pechkovsky excepted, in general, the best Russian singers and dancers were appropriated for the Bolshoi in Moscow, the capital of the country and its showcase for the larger world.

Gurvich did tell me that a major moment in his life was when he went to Moscow in 1964 for the fabled visit of La Scala. Hearing Bergonzi, Freni, Scotto, Simionato, Cossotto, Tucci, Nilsson, Price, Raimondi, Prevedi and Cappuccilli under conductors like Gavazzeni and von Karajan was a revelation; not that Russia did not have its own equivalent artists, but the Western school of singing was as refreshing to Russian ears as was the discovery of Vishnevskaya, Archipova, Obazstova, Atlantov and Lisitsian to Western audiences. People from time immemorial have always appreciated that which they don’t have, and on some perverse level even think that the other “side” might possibly have superior talent, while on another more chauvinistic level, these same persons are certain that what they have, after all is said and done, is really the best. All this is my own speculation, surely not provable; just an observation formed over many years.

as Otello

as Otello

****In 1966 Melodya issued a Medium Play record of some of Pechkovsky's recordings. This release is nowadays hard to find. The recordings go back to pre-WWII except for dio mi potevi which was taken from a live concert in 1957. In 1993 a CD was also released in St. Petersburg combining the recordings on the Melodya MP and some extra song selections.(Ed.)