PIRATES OF THE HIGH C'S (Opera bootlegging in the 20 th Century) by Nicholas Limansky

218 pages; YBK Publishers – New York.

Click here to order the book with the publishers

Click here to order the book on amazon

This is not a book for ordinary opera lovers. This is a book for us; avid collectors of pirated recordings from the mid sixties to the end of the century.

It is not an academic history of that phenomenon but the reminiscences of one of us; moreover one who had intimate knowledge and experience from working for one, maybe even the greatest of pirates.

Mr. Limansky was for a great part of his life a professional chorus and small bit singer and is married to a former opera singer. Therefore he is strong too on the musical side of pirating as well. He and his wife lived many decades in New York and the book is very US- and even New York-centred. Don’t expect mentions of famous European shops like Papageno in Paris, Only Yesterday in Den Haag (The Hague in The Netherlands) or the best known of them all: Michael Thomas in Lymington Street on Finchley Road. The best stocked however was the less known Dimar in Rimini which had a huge and complete official and pirate collection on its big first floor. Hours I spent there though I often grinded my teeth looking at the pricing. The owner obviously was a connoisseur and being an official dealer as well he knew exactly which records were deleted. Each year prices rose on rare commercial issues seldom to be found like Nancy Tatum's recordings or the RCA-issue of “I canti che hanno fatto l’Italia” with Mario Del Monaco, Virginia Zeani and Giulio Fioravanti. It surprises me Mr. Limansky only briefly mentions Academy on 18th Street and forgets entirely Gryphon’s on Broadway (later 72nd Street) in New York.

As could be expected the author starts with the bootlegs of the Metropolitan Opera Broadcast Recordings though some of them were published by the Metropolitan Opera Guild which took care to clear everything with the artists (at least the Guild claimed it had done it).

Things start to heat up when Mr. Limansky writes on his early record hunting. Lucky for us he has a good memory and therefore can put things in perspective. He tells us he bought the 3 LP Vespri Siciliani (Callas) for $30.00 which is now the equivalent of $229.00 . At that time an LP averagely cost about $4.00 and buying pirate issues was expensive. Like Mr. Limansky I often salivated and put the records back on their shelves at Dimar.

Interestingly is his discussion of the great pirate labels; the best known though definitely not the best are the plethora of labels Eddie Smith produced. The author is friendly, too much indeed. His “There were gross pitch inaccuracies and a remarkable disregard for correct documentation” is correct enough though some less friendly people would call Smith a crook. His quality of vinyl was hair-raisingly bad and I remember playing a few sets in the possession of the late Dutch critic Leo Riemens. Riemens had played them sparingly and even then they already sounded worn.

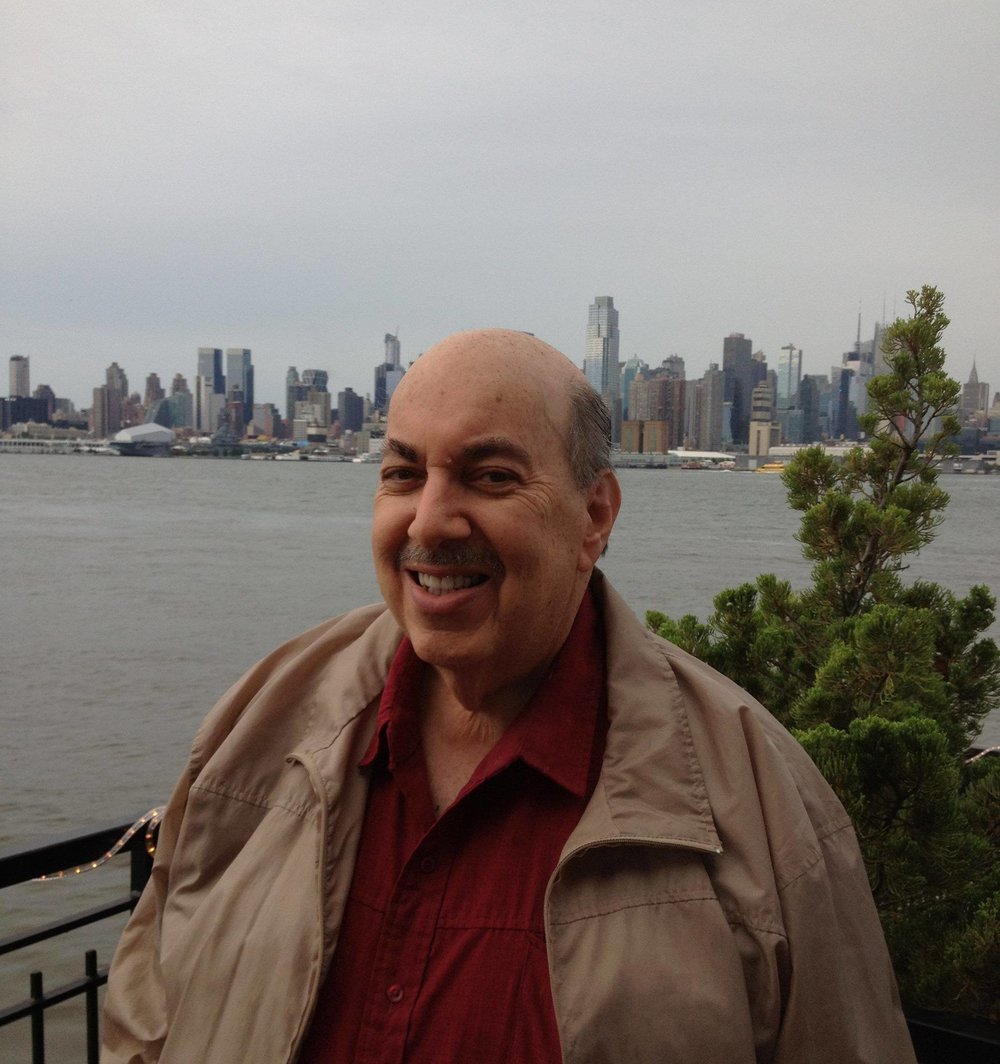

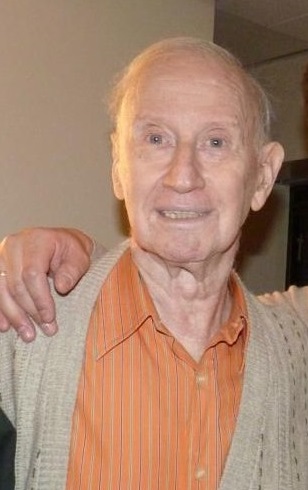

(Martinelli and Eddie Smith)

(Martinelli and Eddie Smith)

For a reason unknown to me a private recording lending firm in Brussels had a lot of Smith-recordings and I duly put them on tape like the famous “40 tenors sing 80 high C’s”; Caruso holding each high C in “Di quella pira” for more than 10 seconds (an early piece of electronic wizardry it turned out while Smith announced it as a great new find).

Mr. Limansky next discusses the more serious enterprises like BJR and MRF. I readily believe him when he writes these labels were put on the market for love’s sake. They too were expensive but the sound quality was excellent and the booklets were highly informative with photos, essays and a line by line libretto with English translation. They were pressed on quality vinyl and my copy of Les Huguenots (Simionato, Corelli, Sutherland) still sounds as new though I acquired it in Italy in 1977 . On those sets sold in Italy the back cover always had a small label stating “cleared with Societa Italiana degli Autori ed Editori”. I still wonder who they paid and if they ever paid artists featuring on those pirates. I would have liked some more information on labels as Voce (Donizetti’s Duca d’Alba and Les Martyrs), VIPS, Discoreale and Italy’s G.O.P.

The most important chapter of the book deals with the 3 New York Tenors of pirating: Charles Handelman, Ed Rosen and Ralph Ferrandina.

(Ed Rosen and Charles Handelman) click here for info on the late Ed Rosen + click here for Handelman's podcast

(Ed Rosen and Charles Handelman) click here for info on the late Ed Rosen + click here for Handelman's podcast

Handelman gets short shrift and I never ordered with him. I remember some posts on opera fora which quoted his less than polite mails (“Hey dude!!”) when someone was not too happy with his products. Ed Rosen I often dealt with though I didn’t start out with him. My first source was an Italian. Italians can be charming even as they try to embezzle you. At the end of the sixties the guy asked quite a price for reel-to-reel tapes which turned out to be not so rare . The buying soon ended when he delivered half an Elisir d’Amore with Bergonzi and never came up with the second half. A pity as the tenor was in fabulous voice and even better than in his well known recording which later appeared on video and Ed Rosen’s pirate LP label. Anyway the Italian delivered me a small treasure which as far as I know still has not appeared elsewhere: Verdi’s Inno delle Nazione sung on RAI televsion in 1968 by Carlo Bergonzi (the Italian guy added some screen shots as well); commemorating the 100rd anniversary of Toscanini’s birth).

My source for his address was the British "Opera Magazine". Editor and owner Harold Rosenthal would never have allowed a discussion of one of the sets offered by the pirates (though he was an ardent admirer of the best selling lady on those lists: American soprano Sophie Cecilia Kalos better known under her Italian artist name). Rosenthal was dependent on the advertisements by official record companies but he knew very well the contents of “ unbelievable treasures” offered in the small advertisements section. That’s where I learned of Ed Rosen’s treasure trove.

Allow me a small digression. From 1968 on I went on a yearly pilgrimage to Verona. In 1974 I was at a performance of Tosca (Domingo, Santunione, Mastromei) when a very American and very Jewish lady made her entrance on the prima gradinata. She had a portable cassette recorder with her and started to play it. Italians can be aloof when they don’t know you well and it takes a time before they start being chatty. They were clearly not interested but I was. I recognized the voice of Richard Tucker; a so-called second rate tenor by Philip Hope-Wallace in The Gramophone. Apart from Joseph Calleja on his best behaviour no tenor nowadays reaches up to Tucker’s knees. I started talking with the lady and she told me she came from Israel where she attended a Tucker concert. She had recorded it for her friend Ed. Not Ed Rosen, I asked? She was surprised I knew his name and I told her I regularly bought reels with him. In earnest she said she didn’t believe it. Ed was only a fanatical collector and never sold things. In those paper-happy days and by sheer coincidence I had a copy of my latest payment as proof and she uttered the kind of expletives that were censured on the famous Nixon tapes. My story matches with Mister Limansky’s opinion of Ed Rosen: ”business ethics were questionable”, “poor customer service” etc. To give Rosen his due I never didn’t receive what I had ordered. True, the sound was often not pristine but I’ve no complaints. I never ordered tapes with items that would in later years be exemplary rare. Later on Rosen had a lot of LP/CD companies and as they were all to be found with Dimar I bought them in Italy until 1985 when I regularly started visiting New York. I still have one of Rosen’s first LP’s: a pirated collection of live arias by the then promising tenor Josep Carreras before his first recital appeared on Philips. And I still treasure Bergonzi’s only recording of Il Corsaro.

Mr. Limansky tells us Ed Rosen and that other great pirate Ralph Ferrandina (Mr. Tape) detested each other “mainly due to a strong clash of egos”. I’d loved to have read more on that clash. Interesting notes reveal the ways Rosen and Ferrandina got their huge collections: often by having a network of other pirates all over the Western world who sent them everything in exchange for items. As far as I know they had no selling colleagues in Europe.

A collector as England’s John T. Hughes rarely went to a performance or a concert in Londen without recording it but I never heard he made a living of it. In due time I noticed Mr. Tape’s advertisements as well and started ordering. There is only one piece I got that could nowadays (maybe) called a rarity as I haven’t seen it elsewhere: Rossini’s Petite Messe Solenelle with Carlo Bergonzi and Martina Arroyo. The pages on Mr. Tape make fascinating reading as the author worked for many years in Ferrandina’s service. He probably made the copies I still own. I know now among other things that there were 26 tape machines in the office, that copying was done at double speed (though the buyer could play it at normal speed at home) and that there were about 6.000 tapes one could chose from. Most tapes were of good quality and are still playable. Imagine the horror of Limansky when one day he entered the office and saw only empty shelves. All machines, all tapes had gone. Later on it became known Ferrandino had an extra business he handled himself: copying video cassettes of American Ballet performances. The company filed a complaint and the FBI closed the plant. Pirate recording didn’t end as Handelman and Rosen continued their business. The author assures us that for a time there were at least three persons recording every performance at the Met. He tells some amusing anecdotes on the do’s and don’t do’s of recording. That reminds me of the Editor of this site being a pirate as well for a few seasons. I still have cassettes from Liège concerts by Vesselina Kasarova, Vincenzo la Scola and a complete Amsterdam Luisa Miller with Shicoff.

After the Mr. Tape chapter the author somewhat meanders on the rarities he himself collected and his penchant for Maria Callas. He gives some advice on the current pirate scene and the online stores where you can find rare items. In the second part of the book he devotes interesting pages to “The two pirate queens” Magda Olivero and Leyla Gencer: both ladies with only a few official recordings (Mr. Limansky doesn’t seem to know Olivero’s official Sacred Arias and her Liriche da Camera recordings). Anyway I can confirm that Olivero herself was very proud of her “Regina” title. When I was her guest in her villa in Locarno she happily told me she had just received a fine copy of her Mefistofele.

The author discusses in detail the singing technique of the ladies in question, their strengths and their weaknesses and their pirate recordings. He then sails on to another favourite: Leonie Rysanek and her many recordings. He finishes his book with an updated interview with Roberta Peters. Interesting to read his opinion on the impression she made in the theatre and the far harsher wiry and pinched sounds one hears on her records. Hers was a voice not kissed by the mike. All in all an interesting read (with too many typos) for us, older and now disappearing collectors. I refer to a piece by Joe Pearce in The Record Collector remembering how once upon a time there were two rivalling collector societies in New York. Finally they had to merge due to a lack of fresh blood and nowadays there are almost no members anymore younger than sixty. The movie “Gone with the wind” starts with the famous sentence: “It was a civilisation gone with the wind”. I fear the same can be said of vocal collectors.

Jan Neckers