CHARLES JAHANT ----- AN APPRECIATION

By Charles Mintzer

How often in life does one meet a remarkable person, a person who opened doors and in some very important ways changed your life? Charles Jahant was such a person, if not a life-changer, at least a life-enhancer. For those of us who love singers, opera history and its lore, one could not do better than coming into contact with this remarkable man. I feel strongly that it is about time to honor one of America’s great historians.

In 1978 I finally met Charles Jahant, a man who I have called on several occasions America’s leading historian of operatic performance. A little history: over the years I was researching the life and career of Rosa Raisa, the first Turandot and dramatic soprano star of the old Chicago Opera for I book I hoped some day to write (which I did in 2001). I tried over the years to communicate with anyone who I thought might have information or remembrances of her. I had seen Jahant’s name listed in the acknowledgments of many opera biographies, but especially the Lillian Nordica, Yankee Diva. I had asked persons connected to the “opera history mafia” about him, and was told that he was “difficult” and they thought he might not even answer me. Fair enough. I managed to secure his home address and did write to him, with specific questions about Raisa. I must have hit a very sensitive nerve as he answered me immediately a three densely-typewritten page letter; he absolutely adored her and better yet he had heard her several times in Chicago, Cleveland, and his hometown of Akron, Ohio. He sent me dates and casts, some of which I had not uncovered on my own. He said he would have to charge me for his help, but the mere $25.00 he asked was almost a tease; I think he wanted to feel that his life’s work had some monetary value.

It is he who encouraged me to seek out Robert Tuggle for photos (this evolved into a thirty-plus year collegial friendship), and it is he who suggested I contact Carol Longone, then almost ninety years old, Raisa’s one-time concert accompanist, living in New York, who he thought might like to talk to me, and it was Carol in turn who put me in touch with Raisa’s sister, Frieda Goldenberg who lived in New York City, who would talk to me about her sister, and this opened up several contacts with Raisa’s family. He invited me to his home in Landover, Maryland, in the Washington D.C. suburbs. I would visit him almost ever year until his death in 1994. So one letter opened up so many important doors in my research efforts, and in turn I got to know this remarkable man, and eventually we considered each other friends. In the sixteen years of my correspondance and visits we never exchanged photos, and I regret I haven't been able to locate one to illustrate this essay.

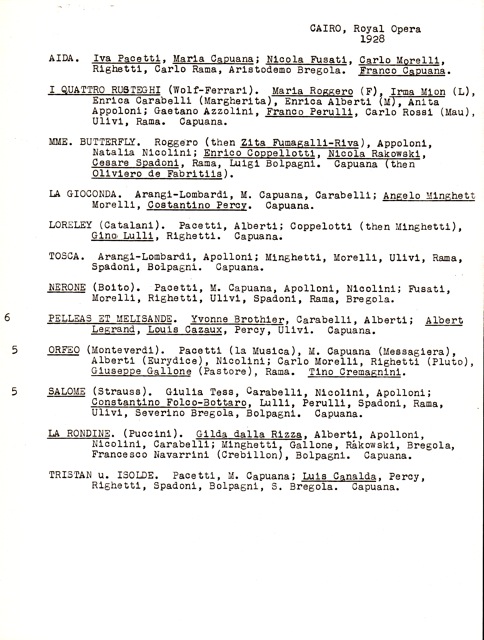

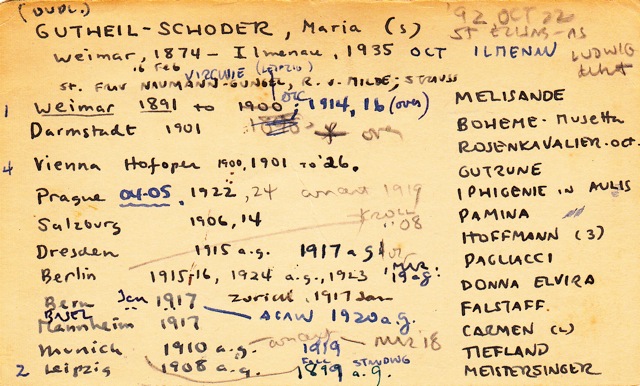

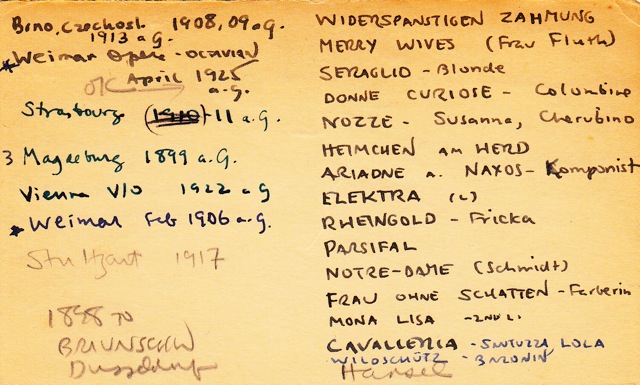

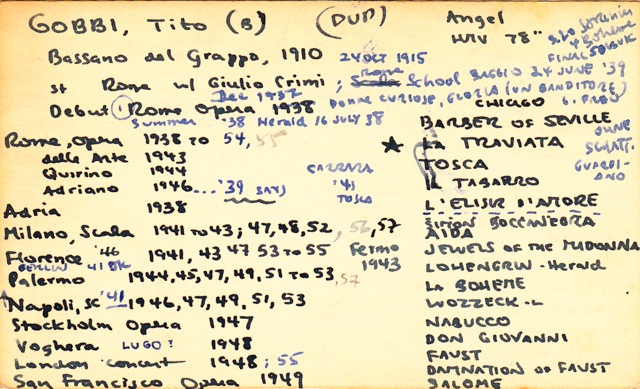

My research was only the starting point. At his home in Landover, he proudly showed me his holdings of opera house chronologies from all over the world that he had compiled through scrupulous newspaper, library and archival research as well as his singer index cards (about 20,000 of them) with incredible career and personal data. It makes me think of Mozart; where on earth was there time to compose all that great music in his short life; just the act of writing the notes takes so much time, forgetting entirely the inspiration and the quality of what was being written. Not only did Jahant write so much, but his transcribing data from the actual newspapers (rarely from microfilm) in libraries around the world, but mostly at Washington’s great Library of Congress, was informed against a full life of travel, attendance of performances and a rich personal life.

Talking with Charles could be a draining experience because one subject would lead to another and when you opened up his mind and curiosity, facts (mostly accurate, but not always) would pour out in a stream, interlaced with social and political commentary. Not only did he seem to know everything about every artist one could think of, but he also knew nationalities, ethnicities, name changes, early struggles, intrigues, gossip, sexual proclivities, as well as artistic stature in realistic terms. His vast knowledge of art and literature plus having been a world traveler informed his opinions. He could be exasperating as I tend to mangle foreign words and names, and he was a stickler for accurate pronunciation. I had asked him for his assessment of French soprano Genevieve Vix. He pretended to not know about whom I was talking. I pronounced Vix like “Vicks throat lozenges;” he corrected me in a derisive voice, saying, “oh! you mean VEEKS?” I then learned that in addition to her considerable operatic achievements, she was also a mistress of the king of Spain.

When one considers that Jahant’s encyclopedic work was accomplished in an era before word processors, photocopying machines, and more importantly computers, it is all the more remarkable. However, there was a sophisticated computer lodged in his brain, because when one engaged in conversation about singers and opera companies, his memory was phenomenal. Only in his last few years, well into his eighties, did I notice any diminution in his memory of facts or the ability to coordinate facts correctly, or as I used to say: “connecting the wires.” As many of us get on in years, one’s attendance at operatic events slows down, partially because it is not as easy to handle the hustle and bustle of going out at night with transportation and other issues, but somewhat justified because one has already in one’s life heard and experienced so much. Not Charles Jahant. His enthusiasm for new singers, stagings, and interpretations would not yield to age. I remember his delight in hearing the young Richard Leech, bringing tears to his eyes thinking of resemblances to Jussi Bjoerling for the radiant freshness and ease of his youthful tenor. In his occasional reviews for Opera (UK) and Opera News he rarely dazzles with details of his vast historical knowledge, but that all-encompassing knowledge informs his very sober judgments. That is why his reviews for these publications, even the cursory or heavily cut ones, have value.

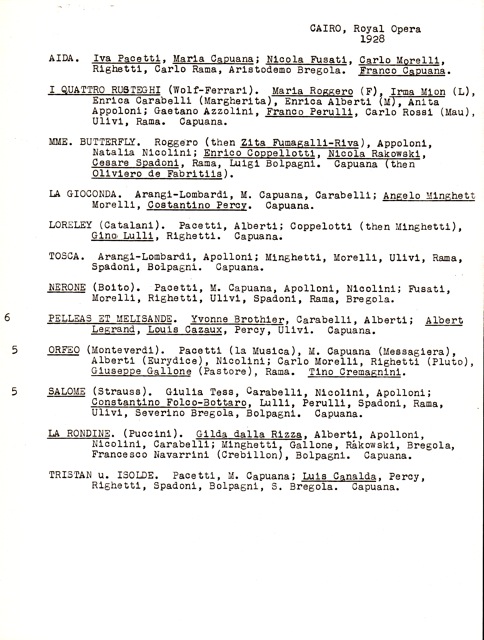

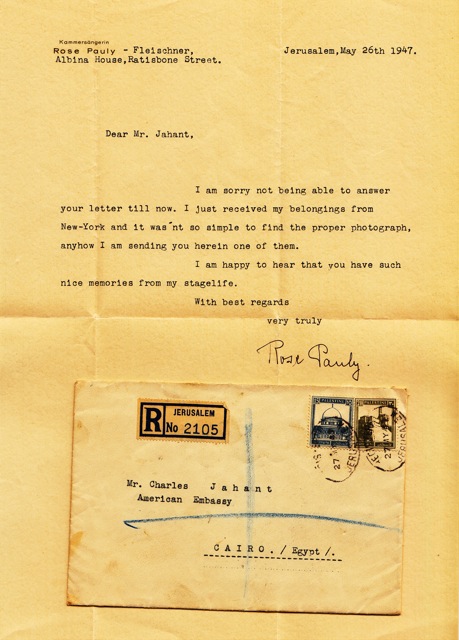

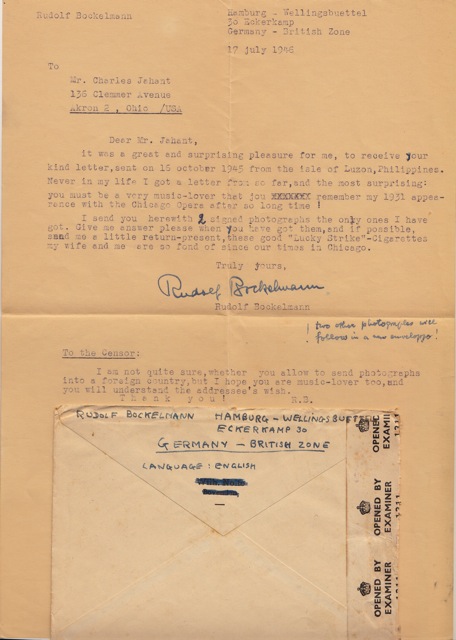

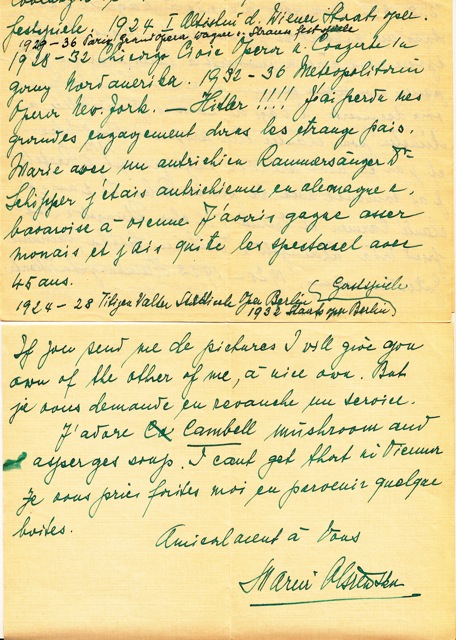

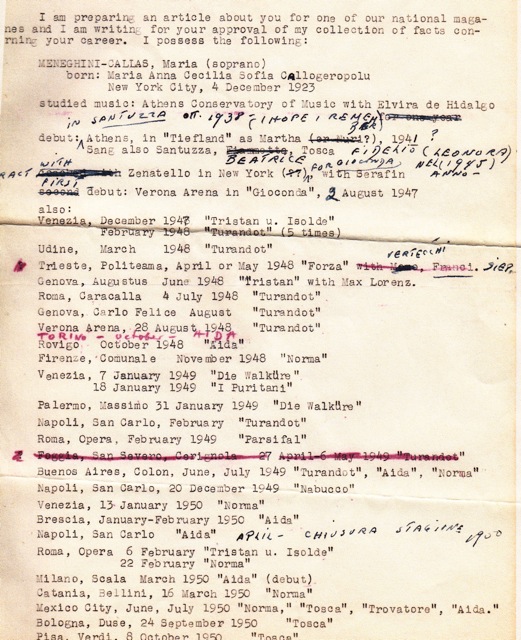

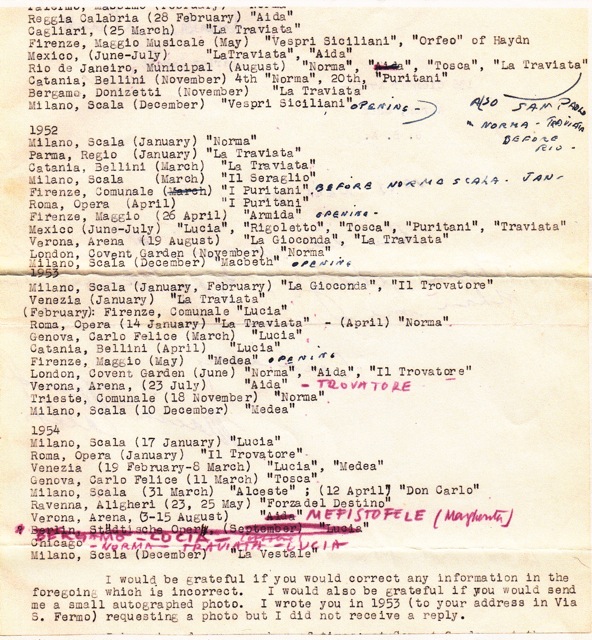

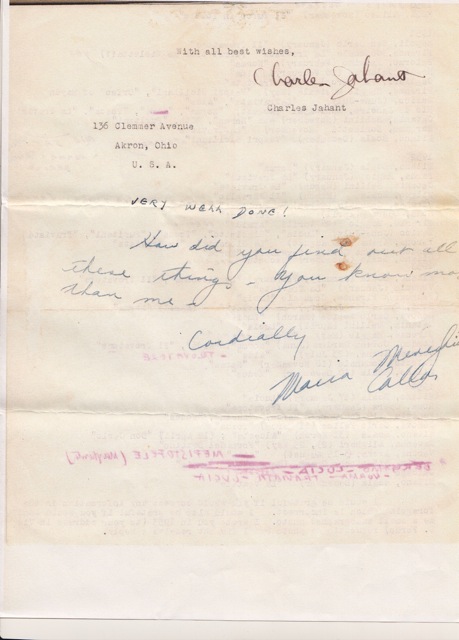

Jahant actually sought out and liked talking to singers, and listening intently to what they told him. I am sure he asked them probing questions, as I am sure he discretely gave the artist some historical tidbit to ponder. He carried on a large correspondence with singers, both active and retired, and I am lucky to have some of those remarkable letters. When serving in the US army in the South Pacific during World War II he continued to write to artists with probing questions about their careers. Shortly after the war he wrote to Wagnerian bass-baritone Rudolf Bockelmann in Germany for information and an autographed photo; Bockelmann’s response, with military censor stamp on the envelope (Bockelmann asks the censor to allow an innocent opera photo through), was generous with fond remembrances of his years at the Chicago Opera. He waxed on about his fondness for Lucky Strike cigarettes and asked Charles to send him some. His letter to Maria Olszewska was answered in what I am told is not-so-good French with some English thrown in with a paean about Campbell’s Cream of Asparagus soup, and his correspondence with Emmy Bettendorf was sad as she complained, as late as 1948, about post-war hardships in Berlin and that some of his promised food packages had not yet arrived and she suggests that in the future he send her help through the vary reliable CARE organization. There is a 1947 letter from Rose Pauly, living in Jerusalem, but officially at that time Palestine and so stamped. [The Palestine stamp was in English, Arabic and Hebrew). He asked Geraldine Farrar about the American soprano Frances Rose who sang in Berlin when Farrar was starting her career there. She told Jahant the little she knew about Rose, but indicated with obvious glee that when she (Farrar) sang Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, her Venus was not the usually-cast Rose, but her rival and big star EMMY DESTINN! with whom we know she shared one of the all time opera enmities. In 1954 he sent Maria Meneghini Callas a tally of her career up to that point, with many of the then rarely-known appearances listed. She corrected some of the information, but was amazed that someone had uncovered so much about her: “How did you find out all these things – you know more than me – Cordially, Maria Meneghini Callas” Remember, this was 1954 and the flood of Callas books with this very information had not yet been published. He uncovered some of the rare early dates for Henry Wisneski, whose early Callas book is still one of the very best, and if I am not mistaken, his book was one of the first to publish some of Jahant’s facts.

(scroll down for the Callas letter, ed.)

Charles gives some of his biography in a letter he wrote to the late Gerald Fitzgerald of Opera News on March 20, 1988: “I am of Franco-Irish family. My Father’s family is French back to the 12th Century when they moved from Liege in Wallonia. I recall that during WWI we flew both an American and a French flag. My mother stemmed from Newry (just over the border into British Ireland) and Armagh. Both parents loved the theater and music.” His French grandmother was an accomplished seamstress and Charles had studied art; therefore many astute and detailed references in his letters to costumes and fabrics. Charles, born in 1910, was raised in Akron, Ohio. His father was an inventor and manufacturer of radio parts. When Charles was growing up larger medium size American cities like Akron had a rich concert life, major artists crossing the United States would often give performances there. And there was Cleveland not so far away, one of the largest cities in the country with annual visits by the Metropolitan Opera and frequent visits by the Chicago Opera as well as smaller touring companies. “I heard everybody: Melba in 1923 in the Public Hall (4000) a week after Garden sang in Public Auditorium (under the same roof!) to 10,000 plus. Tetrazzini at the Paramount in 1935 (I think), Calvé in Keith Vaudeville in 1926, Gadski as Sieglinde with Sembach 1930-31. At the question and answer part of one of my lectures a young lady asked if I’d ever heard Flagstad and Melchior. I said “many times.” At home I counted: Flagstad 79 and Melchior 87 times.”

He heard as a young man Rosa Ponselle sing Aida three times in Cleveland on Met tours (1924, 1926, and 1927) more in that role than a New York City Metropolitan Opera regular attendee heard (she sang Aida only twice in New York at the Met). He was able to elaborate in detail the relative merits of the Ponselle, Muzio and Raisa Aida’s as he heard them all in their primes in the late 1920s. In a letter he wrote to a fellow researcher (I have the carbon copy): “One heard so many people with both the Met and Chicago that the performances, without programs to refresh the mind, become mixed up. I heard Raisa, Muzio and Ponselle all as Aida and Leonore (the first was my favorite – again, I can see her from her first entrance). Muzio was an interesting, sympathetic Aida, with her long blue veils which she manipulated beautifully. Ponselle at this time was awfully posey. Her voice saved her. I heard her Aida three times in Cleveland. Muzio as Santuzza was horribly overacted. I preferred her in “Forza” and “Chenier.”

Jahant, and his partner Richard Fletcher, were both huge admirers of Mary Garden and had a long-standing project, to write the definitive biography of the great diva. Fletcher especially corresponded with most of her still-living colleagues and there are amazing letters from them about her unique personality and art, mostly glowing. Jahant had a huge collection of rare Mary Garden photos, many of them just different takes than the published ones. He claimed to have “bombshell” information about Garden’s early years in Paris that if ever published it would have put Garden’s career and persona in a slightly different light than we now have. He loved to puncture myths with researched truth and he did tell a correspondent: “Mary Garden got a lot of mileage out of a sudden debut [‘Louise”]. She claims to have made her debut on Friday the 13th, on which day all Paris theaters (it was Good Friday) were traditionally closed and in seat 13. I have a quote from Vizentini, the regisseur, who says he gave her a Loge ticket 114”…and apropos a trip to Venice in 1904 where she claims to have heard “Bohème” at the Fenice…”But she couldn’t have heard “Bohème” at La Fenice because the theater wasn’t operating that season. And her two children!” Upon reflection I am almost certain now that the “children” revelation was the “bombshell” with various theories as to the identity of the father and how Mary successfully kept this fact out of the public prints.

I never did know for a certainty what Charles did for a living, or rather what was his source of income. I have surmised that after military service in World War II he was doing highly secret intelligence work for the US government in the Middle East, and that would explain Pauly’s 1947 letter to him care/of the American Embassy in Cairo. I know that in the late nineteen-forties and early nineteen-fifties he lived for long periods of time in the Mediterranean basin and spent significant time in both Egypt and Italy. He told me that in Cairo at the opera house, the archivist gave him free run of the archives, and he produced an excellent chronology of that theater. Yet he went to London and heard most (at least, five) of Callas’ Normas in 1952. He was part of the Metropolitan Opera’s European agent Roberto Bauer’s circle of friends in Milan where he met many important Italian singers, active and retired. Yet, most of his correspondence is addressed to his family home in Akron, Ohio or later in Landover, Maryland. I know that starting in the mid-nineteen-fifties he and Richard Fletcher set up a home in Landover. Fletcher had an important job with the US Department of Labor in Washington, and Charles spent most of his time at the Library of Congress doing his research. That is about as much as I know for a certainty about his personal life in his prime working years. I have no idea when Fletcher passed away, but it was clearly before I met Charles in 1978.

Early in my correspondence with Charles (4 April 1978), he explained himself, his scholarship and what generated his work: “Now to your letter of the 17th. Like you I am a compulsive researcher. I went into this game serious around 1932 when I began getting leaflets from the Chicago Historical Record Society. The writing was by the famed Leo Riemens who would write that if Magini-Coletti had ever sung in America he would have been regarded as greater than De Luca, Ruffo, and Sammarco put together. He had and he wasn’t. L. R. was ignorant of the fact that Supervia had sung here for two seasons (one in concerts only) at that very period; so many other gross misstatements that I began to collect information about all our U.S. companies: Boston, San Carlo, Lombardi, New Orleans, St. Louis, Aborns, Strakosch, Maretzek, Ullman, Associated Artists, Savage, Hess, Abbott, Kellogg, Seguin, Philadelphia, San Francisco from 1852, etc. etc. Yes, Minnie Hauck, the first Deutsche Oper of the 1840s and that of the 60s, plus the Charlottenburg Opera of the 1920s/30s, the Russian Opera. I grew up partly in Akron/Cleveland, Chicago and New York, and I always had excellent libraries nearby. I have an almost complete day-by-day Met history hand-written dating from high school days. Plus tours that are more complete than Miss Eaton’s “Caravan” – and more correct, let me say. I suppose there are still errors in the Seltsam. I remember that he listed a “Tristan” with Schorr as Kurwenal. I saw the performance, and it was Schutzendorf, short and rather roly-poly, whereas Schorr was about 5’9” and always recognizable because he had a thick lower lip which always showed through any beard he wore. And Gustav S. usually squinted. Cleveland had papers from Paris, Buenos Aires, Rome, Frankfurt and I had a field day there. In New York I’d sometimes show up at 9 a.m. and work straight through until 9:30 p.m, with only breaks for a Nedick’s egg salad sandwich and a chocolate milk and some Hershey bars, which were a lot better then than those of today. I did the same in Chicago. Later I was to work in the National libraries of Rome, Florence, Naples, Madrid, Lisbon, the Brera in Milan, the big libraries of Paris (plus the Opera), Vienna and so forth. London I had done in Libraries in Melbourne, Brisbane, Capetown, and Johannesburg, etc. I told you I have the lost Cairo archives here at home. I also worked in many theater archives: Franco Armani let me have the run of La Scala, and so did Comm. Levi, a dear old man in his 70s at the time in Rome; Sofia, Prague, I don’t know where all.

My object was always to set the few truly great performers in their proper place, surrounded by the mediocrities, even down to comprimarii – though Alice d’Hermanoy was a secondary singer of some distinction who stemmed from Covent Garden (I’ve never owned the Rosenthal Annals; I doubt he lists her performances or those of Minnie Egener, whose parents and grandparents had been singers. D’Hermanoy, incidentally, had been a leading mezzo in Brussels (Park Theater), Liege, Geneva, Lausanne, etc. She was the wife of Charles Lauwers, assistant in Chicago, but also a conductor from time to time.”

Charles could be very frank with his advise to the current crop of singers. In a 25 April 1983 letter to a friend of Susan Dunn’s (he addresses her as “Dear Connie”): “I agree with M. (Matthew) Epstein. Don’t let Susan reduce, or the voice will be altered in some way. This has happened to numerous singers. It happened with Rosa Ponselle, who lost, I think, 30 pounds for her Carmen. She looked wonderful, it’s true, but the voice lost a little something, which it regained during those years she wasn’t singing, but drinking because of her unhappy marriage. Do you know any of her discs? My favorites of all are the “La Vestale” selections. What calm! What poise! What beauty! Interesting that Susan should have auditioned with the first of these. Excellent choice….I first heard Callas (and met her, as I may have written) in London (18 November 1952). I took the Queen Elizabeth over especially for that purpose. She weighed 250 pounds. Later that same season at La Scala she was down to the famous figure we all know. Bing’s European agent told me she had taken a tapeworm (under medical supervision). In London the voice was big, though not huge. It reminded me then of Ponselle’s in size. Several months later the voice was reduced in size and had overdeveloped the famous wobble. So: no great reduction in size for Susan Dunn.”

In the same letter in a different context he talks about his photo collection. “It includes almost 70 photos of one of my early favorites, Rosa Raisa, the first Turandot. This was the first Supervoice I ever heard, so powerful that it made my ears wobble. That was 1926 with the old Chicago Opera (since then I have heard three others: Eva Turner with the Chicagoans also, Caterina Mancini in Rome and Florence, and Suzanne Juyol at the Paris opera). Not that loudness is a criterion. I don’t consider Birgit Nilsson, whom I can’t stand really; her publicity must have cost her as much as Mrs. Sills’s.”

In an earlier letter I had asked Jahant about other powerhouse singers, ones that I had heard: “Re Raisa’s power: I have (or had) extremely sensitive ears. The singing of these ladies (did I mention Ulysess Lappas, the tenor) set them to buzzing, almost to wobbling. I’ve heard all the singers you mention: Flagstad, Farrell, Nilsson, Tebaldi, Milanov, Cigna. None of these had any such effect on me. Nilsson had a cutting edge and a certain power which I never liked (perhaps you are one of her many fans, but I was unmoved by her, as I was by Albanese and Tebaldi). Flagstad had power, but apparently not enough to move my ears. Traubel, too. Cigna’s voice wasn’t all that big, nor was Milanov’s…It’s impossible to describe a voice. Raisa’s was golden bronze, purplish. She was often (unjustly) compared to Ponselle. I loved them both, but in very different ways.” To Fitzgerald he elaborated: “Raisa had the most powerful female voice I ever heard; Eva Turner wasn’t even in the running; Rosenthal et al. have ballooned her reputation beyond believability; she was stiff and awkward as an actress; I rather liked her, though. Her bass speaking voice is a later development. Part of the charade.”

Charles, like many very knowledgeable people, could be both absolutely brilliant one minute and full of contradictions the next. He had a generally “down to earth” philosophy and mingled easily with his neighbors in a predominately middle-class African-American suburb, but he could also in his letters reveal the social snob, impressed by invites to prominent Georgetown homes and meeting “so-called” very important people. He would talk in an elevated way about his gardening skills, but the next minute he would talk about his investments and his tax problems, always tax problems. I am certain he was a Franklin Roosevelt Democrat, but shared many Republican values. His contradictions were the same as with many people, and this made him fascinating; you were never sure. Even in his research he was very competitive. Others working in this field he considered his inferiors. He did not have good or easy relationships with others compiling historical performing data; even if their work was in some respects better or more detailed than his, he could always feel superior because of the depth of his life experience, the wider scope of his interests and curiosities, and the level of his cultural attainments. He desperately wanted recognition for his life’s work, but he did not make it easy to be his friend. In the almost twenty years I knew him, only on a few occasions were there misunderstandings or bumps in the road. He knew that I truly appreciated the depth of his work, and I think he was grateful for our friendship. Perhaps, on some level he thought I might perpetuate his legacy. He had another quality that was very disturbing, and I have found this true in other geniuses. He looked at another person’s work only for its mistakes, and was not shy in pointing them out. He loved to play the “expertise” card.

In the late 1980’s Charles went back to Europe for the first time in many, many years. I have a letter (I kept all of them) from Brussels dated Saturday the 24th, no month or year. “Dear Charles, London was so expensive it knocked me out, and I was told Stockholm was even more so. So, after five days in the UK, I went to Antwerp. It’s a charming, pokey place. A second-class hotel charged $40 per night. Just missed “Parsifal” and (purposely) “The Bartered Bride.” The Direction of the Opera treated me royally, were apparently impressed by my knowledge of their past history and presented me with a souvenir book of the house. It has hundreds of omissions including Mrs. Litvinne, who with Van Dijck sang T&I on 16 and 20 December 1910. She isn’t even listed on the roster for that season. It was the same here in Brussels – everyone is kind. I was given another book on the Monnaie which is abysmally mis- and un- documented shockingly. I was too tired to go to “Coq d’Or” (with Bruce Brewer) last night. Will go tonight for Suzanne Sarroca’s MONO-drama. Found a shop with postcards of Garden, Eames, Farrar, Calvé, Caruso, but they-re outrageously overpriced. I got a Mazarin, a Drill-Oridge, a Delna and half dozen others for around $1.00 each, whereas José Danse, baritone of Hammerstein’s London season, goes for around $7.00. I asked why and the proprietor pointed to a book with suggested list prices. There were three Félia Litvinnes – two Isoldes, Brünnhildes and a ferocious Armide about to lunge at the viewer. At $7.00 or $8.00 each I didn’t want to buy them, even for trade, as I have 3 of her in my collection. Made the acquaintance of an Aussie sailor in Antwerp, nice but foul-mouthed. Visited friends here yesterday and today. Worked a little this morning in old programs for Ghent, Antwerp (1913-14) & Brussels (1897-for Tourneés)…On to Frankfurt Sunday or Monday. Love, Charles.” The reader will notice reference to Litvinne, and that is because I introduced my friend Richard Miller to Jahant, and as I was working on Raisa, he was working on Litvinne. Some of Richard’s Litvinne research is scheduled to be published on Operanostalgia in the near future. By this time Charles and I were on first name terms and he was comfortable talking about his private life.

(Bourskaya in Carmen)

(Bourskaya in Carmen)

I had acquired from the estate of a Claudia Boynton of Chicago, but retired to South Carolina, many letters, photos and papers belonging to her friend, the mezzo-soprano Ina Bourskaya. I always made a point of sharing memorabilia acquisitions with Charles, as he loved these. This elicited quite an informative letter about Bourskaya, and then he segues to the Carmens of his experience: “Yes, I. B. really came to life in the material you so generously sent and shared with me. The American citizenship, the Americanisms in the letter (‘rained cats and dogs,’ ‘gulped’ etc) and the touching care for others display a remarkable human being in an opera singer. That and the education, plus the marriage to an Orientalist make it doubly fascinating. As I said, her voice wasn’t truly remarkable, being plainly Slavic with no overtones, no richness (despite Claudia’s ‘tantalizingly rich’ description). It was her acting that made her a favorite for me. Matzenauer, too fat, and Homer, too emotionless, were my early Azucenas. It took Bourskaya to bring the character to life. I will never forget her capture by Ferrando and a couple of soldiers. She was a lioness, lunging from side to side, eyes blazing (her eyes, as I’ve said was one of her greatest advantages) – I’m sure she must have hurt her wrists. That was in Cleveland, Public Auditorium, probably ’35 with Sarroya, taller than the tenor, Lindi, probably Royer, since I didn’t see Valle that year save in “Romeo” with Sabanieva and Rothier. [most probably the touring San Carlo Opera] I liked her Amneris, but now, looking back, it was almost a parody of Egyptian murals. Nevertheless the 4th Act was thrillingly delivered. She certainly was picturesque in the part. I saw her in “P. Ibbetsen” in NYC – Mrs. Glyn. But didn’t understand a word she uttered. She wore an ugly costume of some material that would be used as curtains in a room at a boy’s school – terrible shade of green. In Cleveland I think it was Wakefield in the role. NO. I just checked and it was I. B! She was my only New York Geneviève [Pellèas], effective enough, but I still see Garden and (Maria) Claessens, holding a long wreath of flowers and swaying to the music so evocatively at the end of Act I. But Claessens was plump and short and scarcely picturesque, except in comic parts. Bourskaya was a touching abandoned wife in the glorious “Sadko” that the Met vouchsafed us in Early Depression…

The Carmen was okay, better than Glade’s, but I preferred Wettergren and Garden, later Castagna and Djanel. Glade was a rose-in-the-mouth Carmen. Supervia was fascinating but wayward. I liked Rosa’s (Ponselle], but I was just about alone in that; it “was” a little overdone. I always admired Olszewska but her Carmen was heavy of voice and person. Swarthout was impossible, Stevens acceptable in a movie-star way. Pederzini, realistic and practically voiceless. Simionato excellent in an Italianate version sung in “French.” Horne, Resnik quite good as was Nell Rankin’s, though untraditional. I didn’t like her first act. She made too much of the rope that bound her wrists. [Marthe] Chenal at the O-C impressive. I’d almost forgotten Farrar and Jeritza, neither of them good though the latter’s death was great. I. B. was better than most, as I think back, and, as I’ve hinted, an actress full of fire. She (Bourskaya) was probably too tall for Cieca, although Kramarich was taller and thinner than Farrell (Chicago, 1959). I stood beside Dalis [the Laura] at the first stage rehearsal and Dalis, whom I’d known when she was a student in Milan, said of Kramarich, “My God! She’s better than I am.” Not true, but amusing I thought. Reflecting on “Gioconda” and wondering why all the Giocondas used to dress the poor street singer so gorgeously. (Usually in the last act). Ponselle alternated dark brown and bottle green, both embroidered. Cigna black and gold, Raisa, tan with fleshy gold sleeves.

In my folder of Jahant correspondence, I found this vignette: “I’ve just read a review of the Cetra “T&I” by André Tubeuf, the most urbane of French critics. On G-P: ‘Grob-Prandl, two tons too heavy (deux tones de plus) and her beautiful and good voice (belle et bonne voix) (displays) a placidity which is deadly to poetry.’ Very perceptive. I heard her twice as Turandot and once as Brünnhilde. To me the voice was strong and clear but unbeautiful…I began to listen to the San F “Jenufa.” After ten minutes I shut it off. It’s good music-to-use-your-chain-saw-by. Janacek would still be unplayed if he hadn’t discovered the xylophone.” I wonder if Charles would have changed his mind thirty years later, now that Janacek is solidly in the international repertoire.

Charles almost defined “free-association.” In his April 20, 1988 letter to Gerald Fitzgerald he writes at length about several singers: “Sayao was another who left me cold. Her greatest moment for me was the Rosenarie In “Figaro.” That was magic. But I was still suffering from Bori-itis, and Sayao’s Manon was too little-girlish, too ‘cute.’ Her finest thing, I thought, was Norina. I could take “L’Elisir” with Schipa and Gigli, even Landi, but not Tagliavini. I left at the half, one with the latter plus Sayao and Baccaloni, even though I admired excessively the latter. In olden times there were bravoes only at the half-price Saturday pop evenings. I remember the first time I ever yelled ‘Brava!’ because I always considered it excessive. It was for Pauly’s debut in “Elektra.” I still have my ticket stub for January 7, 1938, the only one I’ve saved. Kappel (a very womanly Sieglinde and Isolde) was my first Elektra and I can never forget her Mary Wigman dance --- arms flung out to the sides, to the heavens, knees up to the breasts, down and up stairs. Pauly’s dance wasn’t so enthralling but the rest was. It was some time before she came out for a bow, obviously exhausted, her dull grey blouse wet with sweat some eight inches or so. She had to hold on to the curtains as she inched along. That was the first time I’d ever seen Bodanzky take a curtain call. He preferred his applause in the pit. Nice man, Mahleresque.” Re Klytaemnestra in other performances: “There was no other Klytaemnestra than Olszewska (I missed Resnik). She was not only behangt with totems, she was red-eyed, red-mouthed (turned down at the edges) and slightly drunken. Much as I doted on Thorborg, this was It. Branzell’s voice began to give out in the ‘30’s. I once drew an “Aida” in which she substituted for Castagna. The regisseur parlant au publique announced that B. hadn’t sung the role for four or five years. She was tremendous, no vehement gestures at all. That night I revised my appraisal system…I used to hate Warren in his early days of Heralds, Alfios and Barnabas. So rough and wooly. Then came “Falstaff” and I jumped on the wagon. In the early days we had Tibbett as Herald. Then came Cehanovsky with his lisp and thin voice. I know he was a beloved old gent, but he bothered me even in “Manon.”…Never liked Alda. There was some quality in the voice that I detested. And she was so unshapely in those last years. Her head seemed too large for her then body. Larsén-Todsén bugged her eyes excessively. Leider was a ball of fire, intellectual, severe. One of my finest memories is of “L’Oracolo.” Scotti was magnificent, though he mostly spoke the role. Maybe Thomas Stewart could re-do it.”

Philadelphia critic Max de Schauensee was a friend of Jahant’s and one can surmise from Max’s letter from April 29, 1968 the range of their mutual interests: “As always, I was quite staggered by all the things you say. But you must not be “too” hard of people who don’t have your accurate information. There just isn’t the time for most people to make an exhaustive survey as you have done. Many rely on information that has been handed them as truth for the last 50 years and it is not always possible to ascertain the right facts, unless one is on the spot… No, I am not writing anything on (Olympia) Boronat. I have done all I could in this direction. But I am not satisfied with her date of birth. The son and daughter were not quite sure, basing the 1867 guess on the fact that their father was born in 1869 (this they seemed to know) and that their mother (Boronat) was possibly a couple of years older. However, I am sailing for Genoa on June 25 (D. V.) and I may try and look up her birth certificate. How does one go about this? I am sure you would know…Two people whose births I have always suspected are Hempel (1885) and Storchio (1876). I cannot believe that Hempel could be practically bracketed with Lehmann, Jeritza, Leider, Larsen-Todsen and others of that group. And she was terribly vain, though a good singer. Storchio, it seems to me, must have been born earlier because of other dates. Do you know whether Robert Hutt and Louis Graveure are still alive? The latter, of course, must have been a fantastic liar. I saw Rethberg recently. She looks so old and thin (for her)… I heard di Mazzei at the Opéra Comique in 1927 in “Bohème” – an effective voice but a stupid expressionless singer. However, they were rather awed by his high notes there. Bulgaria, I think?...There is no use in lambasting the local opera companies in the matter of “régie.” The Academy [of Music, Philadelphia] can’t be had for rehearsal, the singers arrive late and there is no money for much rehearsal of for elaborate sets. It is not the opera companies but the sickness of our times – unions, too much of everything, people flying about. It’s pointless to sigh about something that, given today’s conditions, cannot be. Better to settle for what we have than have nothing at all. “Grand” opera is a 19th Century exercise. It is a wonder it can flourish at all in this age of slick intimacy and mountain music…Can you clear up something for me that has been puzzling me for ages. Were there two Fernando Capri’s? One sang quite far back, and I heard another at the Met, circa 1916…maybe it was the same man and he drank from the fountain of eternal youth…I shall look for you with pleasure at the “Luisa.” My warm best wishes to you and Dick --- Max”

To the same correspondent, Connie, the friend of Susan Dunn, he expounded on the Handel revival: “We have a very active Handel public in Washington. Each year the choral societies give a three-time Festival. Each time they advertise the work in question as Handel’s own favorite. Saturday night it was “Theodora,” with the same old claim trotted out in the paper and on radio. I was too bushed to go, and besides the singers weren’t of the top dish. Justino Diaz, Lorna Haywood (remember Fiordiligi), Richard Lewis (veteran British tenor who was never very good!) But “Rodelinda” is a marvelous work. It pulsates with drive. The soprano solos (extremely difficult) are the chief glory. And there are at least four, possibly five. If Andrew [Porter] goes he’ll be sure to give Susan a rave.”

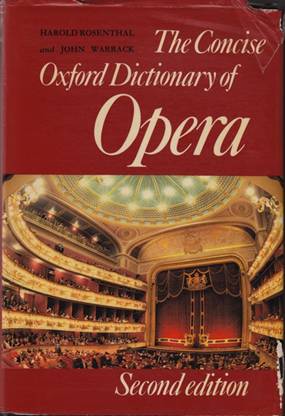

Charles usually opened his letters with apologies for being somewhat late with his replies. It was a combination of true sincerity with some boasting and name-dropping about his “full plate” of the help he is giving to other researchers, plus the problems of life in general. To Henry Wisneski on May 13, 1974: “I can’t believe I haven’t replied to your letter dated the 17th of last month. But I haven’t, and I apologize abjectly. Trying to run a house and garden (apple trees to be sprayed, tomatoes and lettuce to be planted and nursed, iris berers to be.…zoysia dead species to be retrofed, weed seeds to be collected before they spread, gutters to be cleaned of tree-droppings) and then to lead one’s own life – shopping, hunting for gas [this was during the gas crisis) and the like. Then one’s commitments: to Rosenthal’s Oxford Dictionary of Opera (he asks me to send more material more quickly) Grove’s giving me a trickle of assignments (I’m doing Salvini-Donatelli, [first Violetta] all new information, whom they’re never before covered), Peter Hayworth today rather sternly asking me to send him Cologne Jan-June 1920 and all of 1922-23, and inquiring if I can furnish him with Wiesbaden 1924-1927. My other British client (F. Easton) is as patient as an angel, and has placed me on his board of directors for some kind of Easton Foundation. Along with the Earl of Harwood, Eva Turner, and some other genuine celebrities. And Lotte Klemperer is patient also; I’ve almost completed research on her mother, and she bids me take my time.”

In the same letter to Wisneski: “We had “Manon” in French and English last month. I went three nights in a row. There were some cuts, more than I like, but it was an extremely good production, far better than the Met’s. In fact I hadn’t seen a better one since Novotna’s and Sayao’s when I was in the service. Evelyn Mandac sings and acts with great flair; she was out-brillianced by Catherine Malfitano. The latter, unfortunately, has a soubrette’s face and manner. Harry Theyard and Robert Johnson struggled with the tenor’s part, but we had two good Lescauts. Lenus Carlson was quite fine, and Harlan Foss not far behind him. The three girls were done by local church singers and they were extraordinary; I’ve never seen a finer team. The Javotte was superb, high camp at its most acceptable. (The same artist sang Lady Macbeth’s Lady-in-waiting earlier this year and stole the show as far as I am concerned)…At any rate I still haven’t written my review for OPERA. Last week NYCO was here. I went to “Ariadne” with Claire Watson. It’s a very German voice now, and fading. Nevertheless she gave some pleasure with her ripe interpretation. John Alexander was marvelous, I thought, and Patricia Wise a charming Zerbinetta. Niska I don’t think much of. Next week “Idomeneo” with Elly Ameling and Leo Goeke (ugh!) – we had it before with Judith Raskin and John Alexander. Later in the summer, Sills in "Regiment” and Sara Caldwell’s “War and Peace.”

Re The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera: this is my favorite handy volume for fast checking dates, spellings, overviews of opera companies and singers and composers. It was edited by Harold Rosenthal, the editor of Opera (UK) and fact-checked by an array of experts in the field. It cleaned up a lot of misinformation that had been taken as “gospel” for years. I am sure it still has some errors, but it is a paragon of a quick reference work. I have a folder of Jahant’s corrections of many of the entries. Often, just little details, but facts and details were his specialty. In the 1979 edition of the Oxford Rosenthal says: “For the first edition we were especially grateful to Mr. Frank Merkling, Mr. Andrew Porter and Mr. Robert Tuggle, all of whom read the entire typescript and made a large number of useful suggestions; we are no less grateful now to the Earl of Harwood, who furnished us with lists of corrections and suggestions arising from that edition, and to Mr. Charles Jahant, whose encyclopedic knowledge of operatic facts, dates, details, and recherché lore was enthusiastically placed at our disposal.” When Charles finally saw the finished product he wrote me: “So many of the errors in Rosenthal-Warwick II probably came from Riemens. I corrected as many as Rosenthal sent me. But the finished product is disappointing. Not as bad as Baker’s Encyclopedia, which (5th Edition) is frightening.” Jahant’s relationship with Harold Rosenthal was complex. They needed each other even if they got on each other’s nerves. Jahant probably resented Rosenthal’s clout in the British operatic power structure, largely due to the outsized influence of his magazine " Opera",and by extension how that magazine gained impact in America, and Rosenthal probably didn’t care for Jahant’s one-upmanship, his know-it-all attitude. In one of his first letters to me, Jahant says re Rosenthal: “There are hundreds of mistakes in his “200 Years [at Covent Garden].” And he still doesn’t even know that Claudia Fiorentini (if she is in it) and others are British girls.”

(Rose Pauly as Elektra)

Herbert Weinstock, who authored many scholarly books on the bel-canto composers, Belliini, Donizetti, Rossini, and also Handel, was a regular correspondent. Jahant felt a need to explain his letter-writing style: “I won’t pretend I don’t look forward to your letters (one has apprehensive feelings about the possibility of a version of this correspondence geared for a gift-edition circa 1975!) Knowing you must have a very large correspondence throughout the world, not to mention your writing contracts and your job, I try to make my letters as brief as possible. Somehow, though I write as I think and the thoughts come out in much more detailed fashion than I’d like, and I find myself putting too much of myself into them. The point is: I wanted to add a note at the end of the last letter to the effect that you should make the requested reply as brief as possible….And now you’ve gone to all the trouble of quoting, even if only in two languages, for my benefit….I was feeling impish, I guess, when I asked why not to confuse the two Loyselets. My personal feeling is that they are the same person. But, there were four de Baillou women: Enrichetta (Hillarest), (soprano), Luigia (mezzo) twenty years after the former, and, finally two contemporary Baillous, Enrichetta de Baillou-Cabran (still another twenty years beyond), and an unspecified de Baillou-Marinoni, who spread her disasters between Trieste and Florence. There may have been two Loyselets, but I have before me Nino Bazzetta de Venemia’s “Cantanti Italiane.” Under Lorenza Correa he has written: “La treviano coi nomi di Maria, Anna ed altrei: l’atto di nascita dice Lorenza.” If it could happen to Correa, why not Loyselet?”

Charles was also an avid photograph/autograph collector as may be surmised from some of the above quotes from his letters. He told Wisneski” My photo collection is rather haphazardly built up. I concentrated on people I heard here or abroad. It has Dux, Lemnitz, Cebotari, Leider (in French), Hina Spani (ditto), Thill, Olezewska, Lehmann, Nemeth Roswänge, Denise Duval, Fanny Heldy, Ansseau, Ritter-Ciampi, Favero (another Bori), Galliano Masini, Rina Gigli, Toti (a friend of my landlady; I called on her), Pagliughi, etc. Stabile, who lived down the street also. Pertile I heard him in “Aida” at the Scala, when I was 16, with Arangi-Lombardi (whom I got to know, and whom I sent to Ankara, where she died) and Elvira Casazza, an ugly but fascinating mezzo, etc. etc. Reminiscences!” Charles claimed he had heard about the opening for a good voice teacher at the Ankara conservatory and recommended A-L for the position.

Free-associating about his photos, he told Wisneski: “the mysterious Jeritza photo is the last scene from “Frau ohne Schatten.” I’m certain. Not the original Roller costume, but probably a later one when Setzer was doing these slim photos of her (I have an absolutely marvelous one of Fedora, Act II). I liked her. She wasn’t as intellectual as Callas, but she gave a good show. For that period Göta Ljungberg was a more interesting Tosca (Johnson had promised it for her at the Met, and she had 3(!) costumes made, but he reneged).

On another note of interest: “It’ll be interesting to read Harvey Sachs on “Turandot.” I’ve always felt Jeritza was lying when she claimed P. wanted her to create the role. It would seem that she wasn’t. I used to know Gavazzeni in the 50s. He was a very intellectual person and quite serious. I once introduced him to someone saying, “The Maestro has written thirty books.” He corrected me. “No, only twenty-one.” I thought this was delightfully modest.” Jahant, in not completing his thought on Jeritza/Turandot and then segueing to Gavazzeni, is not typical; I think he was going to say that Gavazzeni, as a young upcoming conductor, involved in a small way with the “Turandot” premiere, also doubted the Jeritza claim.

When I first contacted Charles, I was eager for anything he could tell me about Raisa: “I began being taken to opera when I was seven. Among the singers of the great old Chicago Opera whom I first heard (1921) was Raisa and she made an indelible impression on me. I’m still being asked which sopranos I consider the greatest of my experience and I always have to include her. I didn’t hear Ponselle in opera until 1924, and I was impressed by her, too, but in a different way. Ponselle was 100% the singer and a conventional actress until late in her career. Raisa was a singer and an actress too, and she had a magnificent walk (the only one to equal her was poor Anita Cerquetti). I can still see her in Scene 2 of “Trovatore” in Chicago’s magical moonlight effect – which I have never seen equaled at the Met – striding across the stage. And of course, her great entrance in the Nile act, trailing floating veils…During World War II I corresponded occasionally with her and was invited to the Raisa-Rimini home at 920 So. Michigan Avenue (I think that was the address). They had the entire top floor on a not very tall building. On my opening visit I was in uniform with six battle stars, and that must have impressed R.R. because she invited me back. Once she opened the door wearing an apron. She was baking some cookies filled with dates or something. Usually Rimini answered the door. I heard her give a lesson in which she sang the low lines of “Mira O Norma” (which used to be sung in Bellini’s time by the Norma anyway, since the Adalgisa was at that time done by a light soprano)…I sometimes freelance at the American Film Institute, which is housed in Kennedy Center here. Last year we showed a Raisa Vitaphone short of two concert songs (perhaps you’ve seen it). She entered, hand on hip, and bowing right and left to her unseen hearers. The audience laughed, and they laughed at the close-ups because of the gap between her teeth. Even though the break in the voice was slightly noticeable her technique was beautiful. I was rather proud because I had to give the signal for a technician, when we were trying to join the negative and the soundtrack. Raisa was one of our successes. We have a negative of the Raisa-Rimini “Trovatore” duet, but no soundtrack.

In the years he lived in Italy (late 40s, early 50s) he visited Titta Ruffo at his apartment in Florence: “Ruffo played footsie with the Soviets, and spent time there in the 30s and post-War. He gave concerts at least. He claimed they still wanted him to make a film of “Boris” in 47 or 48. He showed me photos of himself as Boris. I’ve always doubted this. He was also a frequent guest of the Czech government, serving as a judge on May competitions, 40s-50s. I heard him in “Otello” and “Tosca” in 1926 when his powers were considerably diminished, since he didn’t make any great impression on me. I also saw the Radio City “Carmen,” which was more than just “brani.” It was about 25 minutes worth of the score with mostly Glade and Lindi. As I recalled it played four times daily for two weeks. Maybe, three times since it was a long show. No, as I told you, the great Ruffo lung power wasn’t much in existence when I heard him. Sved was as loud, if not louder – in Europe; I never noticed his “great” power over here, either. Only in Rome and Florence.”

For someone who was not Jewish, Charles was fascinated by and knowledgeable about Jewish singers. I can charitably say that Charles was not an immaculate housekeeper: “Surprise: I’ve begun to clean my room. One of the pieces of paper contains a few lines that may interest you. It’s headed “The Barilli-Patti Family” and opens” Patti confessed to the writer that Jewish blood flowed in her veins.” Unfortunately, the source is not noted on the yellow page of notes from some American journal. The date is around 1898.” Charles goes into a lot of history of that remarkable family, doubts her official birth date, suggesting that the published birth (baptism) certificate although signed by “Fray José Somebody” was probably the result of a bribe. Grisi claimed she supervised Patti’s baptism before her wedding to the Marquis. Charles was very knowledgeable about the rules of the Catholic Church and says “You aren’t ever baptized twice in the Catholic Church.” It was rare for Charles not to have noted on the “scrap of paper” the source; one of the amazing “givens” of his “modus operandi” was citation of sources, often magazine articles, but almost always dated.

In March 1988 he asked me: “Were you there this afternoon? I have never heard a worse “Walküre” (Behrens, Rysanek, Meier, Hoffmann, Adam). Even the one at the Cleveland Stadium in 1931 with Alsen, Roselle, Georg Fassnacht from Manheim and Alfons Schützendorf with 16 Valkyries riding horses on a treadmill, each extra as bad. True, the Helmwige was pretty good, but she made a mistake toward the end of her section. Even Levine was unusually too slow. I have a new role for Leonie: The Medium.”

Charles was an early “green.” He used a lot of paper in his work, but hated to waste paper. Many of his chronologies are written on the backs of advertisements and other wasteful letters, and he would cut up cigarette cartons to make index cards for the singer files that didn’t need two sides, although I don’t believe Charles ever was a smoker, even when that vice was fashionable.

As one has gathered from my exposition of the depth of Charles’ research, I have only touched on opera performance. He could talk about film, stage, ballet, scenic art, costuming a favorite subject, and stage direction. He was also interested in radio. He kept a diary of what was available on the radio suggesting the riches available on American radio in its “golden era” in the 1930s.

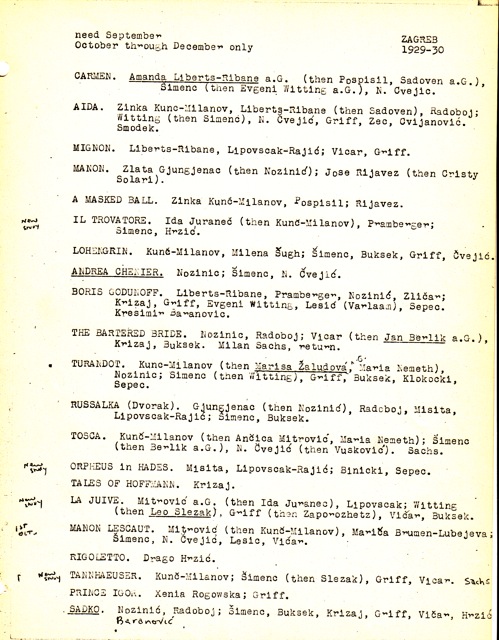

Over the years that I knew Charles Jahant, he was always generous in letting me take some of his precious research files for photocopying for my own enjoyment, reading and use. He impishly said when he let me photocopy his chronology of the Zagreb opera, the scene of the early Kunc-Milanov performances, not to share this information with “Zinka people.” Who on earth did he think would be most interested in Zagreb in the early part of the twentieth century?

By 1994 his letter-writing days were past, and I would periodically chat with him on the telephone. When I was not able to get through to him at a time when I was certain he would be at home, I called the police station of his neighborhood requesting them to send a squad car to his home to check on him. They did and informed me he was in his garden and didn’t hear the phone. But it was also clear that he was declining. A few weeks later, when I called, a middle-aged lady answered the phone and identified herself as Charles’ niece. Charles had passed away the week previous. She told me she was at a loss and needed guidance as to what to do with all his papers, stacks of them everywhere, and she was clueless that her uncle was an eminent scholar in this very specialized field. She was about ready to put all this dizzying paper in a dumpster. I immediately went from my home in New York down to Washington and worked three days partially organizing the “mess” in his house. Stacks of papers everywhere, and the pervasive odor of cat urine. In his last years Charles apparently would take out a singer card or some pages of a chronology, and never put them back in their proper place, and mixed with these miscellaneous pieces of paper were bills, tax statements, and other domestic things, unrelated to his research. I notified Bob Tuggle of the Metropolitan Archives of this situation, and Bob arranged for a van to bring the files back to New York, and they are now safely part of the Metropolitan Opera archives, and they are used for reference and research. I already had most of his chronologies photocopied, and I now have his duplicate singer cards (about eight hundred of them, marked “dup”), the originals are at the Met, and I saved the handful of singer letters that he did not already dispose of. Charles always seemed to need money, or thought he did, and for the right price would sell some of his autographed items. Occasionally a Jahant letter will come on the market from estates. The Callas letter referred to came to the attention of a prominent autograph dealer, who made a copy for me because of my close association with Jahant.

In life there are many interesting people floating around the periphery of the music world, connoisseurs and dilettantes with various levels of knowledge, compulsive attendees, and occasionally a genius like Jahant, one who really knows the history and traditions of what is being presented and can verbalize with great specificity his ideas. It was an enriching experience for me to be counted one of his friends.