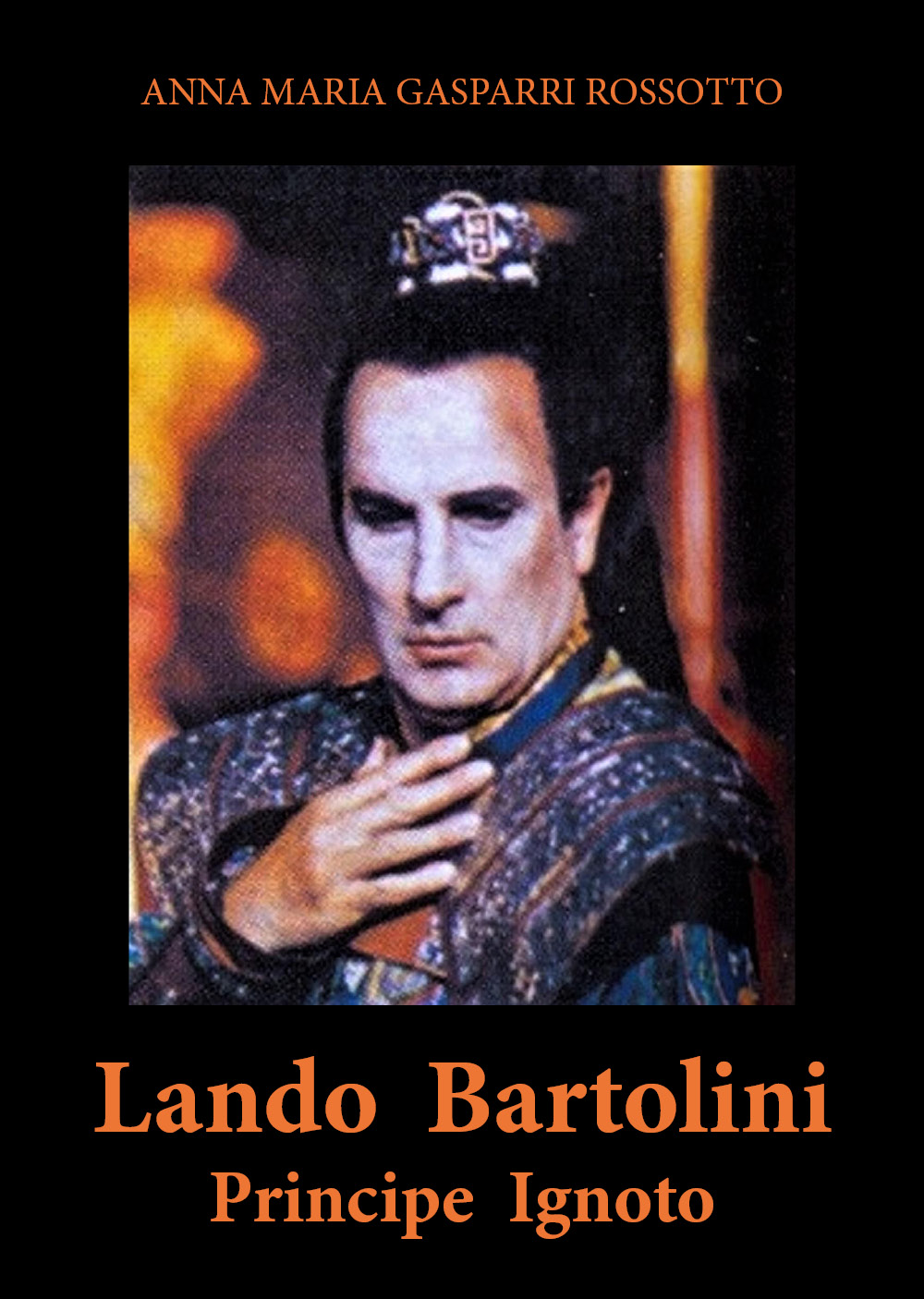

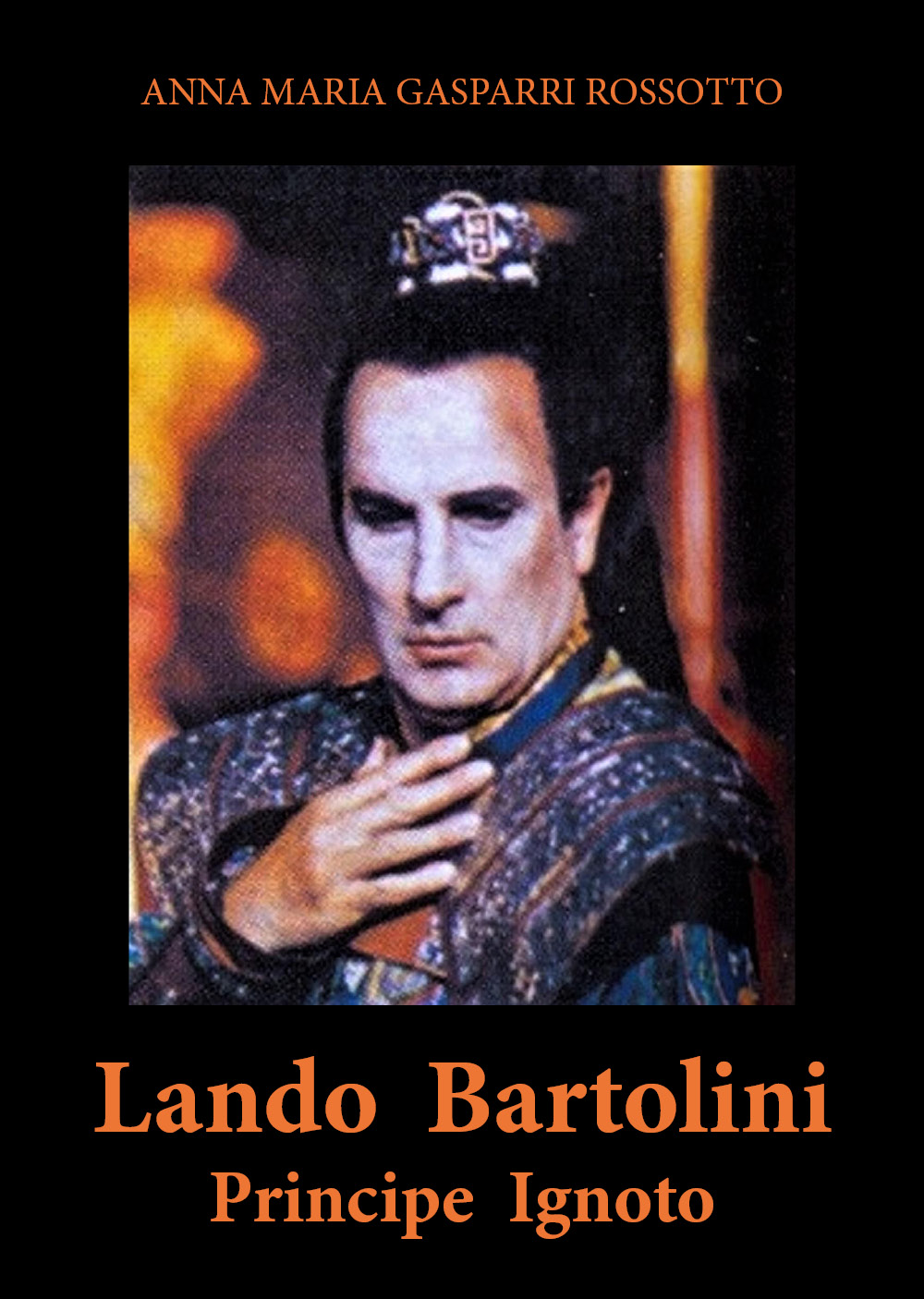

LANDO BARTOLINI "Principe ignoto” by Anna Maria Gaspari Rosssotto

420 pp (including 2 DVD’s)

Click here to order the book or on amazon

The lacking name of a publisher says it all. This is a book produced by the author itself and a pure fan’s work. Still, it is typical for the mysteries of Italian books on singers. Why can't Italians write a decent and honest biography of a singer? (Maybe Italians think: Why do these Germanic-language morons want a singer’s life and career written as if singers were world-changing historic figures?). Are Italians not interested in a correct well researched book that deals with the vagaries of life in the theatre, with highs and lows ?

The book starts with “Lando raconto” telling his migration to the US, studies at the Music Academy of Philadelphia, winning the Mario Lanza prize and making a student-début in Il Tabarro after one year of study in 1968. The tenor continued his studies and in 1973 made his début as a professional singer in a killer role: Osaka in Iris. According to Bartolini from then on he went from success to success. Fine for me, I do not expect a tenor, especially not an Italian tenor, to tell us in detail his failures or moments when the voice didn’t suit the intentions. This goes on for 80 pages (a lot of photographs included!) and then it’s time for the official author to take over and she succeeds in increasing splendidly some nagging frustrations after Bartolini’s ode to himself.

Do not expect a normal chronology whereby you can follow the career, its rise towards the Metropolitan and its decline in smaller theatres. Instead Madame Rossotto gives us for each opera in Bartolini’s repertoire dates, lots of photographs and always positive reviews. The reader -if he has patience- can try to puzzle for him or herself a chronology. If one didn’t know better one could almost assume Bartolini was the toast of the operatic town for two decades. At the Metropolitan he clocked 57 performances; some 40 of them in the house.

Do not expect in this book a discussion of Bartolini’s voice, his strengths and weaknesses. Anyway one can judge for oneself as there are two DVD’s included with extracts from Bartolini performances. These too are mostly fan-recordings as the picture is often murky, the sound is not too bright and sound and picture most of the time do not completely match. It is clear these were recordings made in the house by the tenor’s family or by friends thirty or twenty years ago when camera’s were still not state of the art. Anyway there is substance enough for a balanced view.

As an actor Bartolini was not a great talent though he does more than just standing there and using stock in trade gestures. Of course he was somewhat handicapped by his small figure at a time when the average tenor (and the male Western population as a whole) had grown with at least ten centimetres. Still, for a tenor “voce” is the important raison d’être. Well it has an Italian ring and is unremittingly loud. Do not expect subtleties, piano’s or even mezza-voce. Of his Radames a review in the archives of the Met notes: “When he tries for subtlety he sings off pitch and runs out of breath.” Another reviewer writes of his Calaf: “A standard setting mediocrity, loud, brutish and absolutely uninteresting” while at the same time admitting: “sings in tune, has power and a certain lustre”. One should not forget that most critics in the eighties and early nineties had memories of the glory of Franco Corelli, the exuberance of young Pavarotti, the richness of Domingo in the seventies and the sense of style of Carlo Bergonzi. Compared to them Bartolini was indeed a bit substandard. But for most people in the Italian provinces, in Germany, France, Spain or my own Flanders Bartolini was the real thing; an Italian lirico-spinto who delivered the goods.

Bartolini belonged to that last generation of the once inexhaustible breed we nowadays miss so much. When Pavarotti and Domingo were not available there were still Giorgio Lamberti, Nicola Martinucci, Giuseppe Giacomini and Lando Bartolini; strong voices who had the heft and the decibels to overcome the orchestra and the chorus in Verdi and Puccini. Mozart tenors were not asked to sing Cavaradossi and a beefy throaty German tenor, excellent in Fidelio in a middle sized house, was not called “the greatest tenor in the world”. Bartolini was not well served by recording companies: two recitals (one completely unknown to me with “romanze inedite by Paci-Gheri; and a few complete operatic recordings (best is Zandonai’s I Cavalieri di Ekebu). Rossotto doesn’t’ think it necessary to mention live performances which are easy to be found e.g. the Metropolitan broadcasts with the tenor. In short, a book for die-hard fans only.

Jan Neckers, November 2021